@mrjyn

June 23, 2018

13 Nicolas Roeg Movies Ranked From Worst To Best by Shane Scott-Travis (because i couldn't read it on his site)

All 13 Nicolas Roeg Movies Ranked From Worst To Best

by Shane Scott-Travis

“Nicolas Roeg is a chillingly chic director.”

– Pauline Kael

(François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 [1966], and Richard Lester’s Petulia [1968] rank among his most noted works as DP)

and then later, of course, as composer, editor, writer, and director.

“When I first encountered cinema it was with a sense of wonder,” Roeg told Time Out in an interview back in 2006. That sense of wonder was evident in the first film he helmed as director, the narrative-shattering, censors-be-damned arthouse exercise/crime drama Performance (1970).

Much of what’s present in Performance (which was co-helmed by Donald Cammell) would come to characterize all of Roeg’s finest films; a narrative shell game of skewered chronology; elliptical and often jolting representations of fleeting memories; nightmarish variegations of sound and image, often kaleidoscopic abstractions and juxtapositions like shiny smashed glass once used to reflect the subconscious now reconstituted into Roeg’s expressive idiosyncratic style.

An almost immeasurable influence on many current mainstream filmmakers, particularly those with an experimental angle;

Danny Boyle, Gaspar Noé, François Ozon, Lynne Ramsay, Ridley Scott, Steven Soderbergh, and Ben Wheatley, to name just a few.

The following list examines Roeg’s feature films.

(PLEASE NOTE: absent from this ranking are his numerous shorts, made for TV projects, and Aria, a 1987 anthology film he contributed to), while also elaborating briefly on the societal impact of his considerable and often celebrated works.

If Roeg is a new discovery for you, than treasures await, and if he’s already a name very familiar for you, perhaps revisiting some of this marvelous work is in order?

“Fierce, uncompromising, iconoclastic, dazzlingly original, [Nicolas Roeg] is British film’s Picasso.”

– Danny Boyle

13. Two Deaths (1995)

Adapted from Stephen J. Dobyns’s 1988 novel “The Two Deaths of Senora Puccini”, Roeg’s dialogue-heavy film relocates the action from Chile to Romania, amidst a violent revolution running rampant in the streets, spurred by Communist dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu, near the end of his reign. Running contrary to the upheaval outside is the lush mansion interior of the hedonistic doctor, Daniel Pavenic (the always excellent Michael Gambon), who’s hosting his annual dinner party for his dozen closest friends.

As the revolution rages, only three of Pavenic’s friends are able to make it to the mansion where, as events often do in a Roeg film, discourse turns to sexual obsession. Pavenic, it’s revealed, has a very shocking and psychologically disturbing, not to mention unhealthy, relationship with his house servant, Ana Puscasu (Sonia Braga).

Largely a chamber piece structured around a startling and lengthy conversation, Two Deaths should be more engaging than it ultimately is. Smartly directed, and with strong performances, it’s a relentless and often unruly picture, and sadly only a minor one in Roeg’s otherwise remarkable canon.

12. Puffball (2007)

Potentially a fan’s only affair, Puffball employs Roeg’s requisite stock of frightening imagery in this deeply unsettling, supernatural-tinged tale of Liffey (Kelly Reilly), a young architect relocated to the bucolic Irish countryside with her fiancé Richard (Oscar Pearce) where she plans to refurbish and restore a long gone to waste cottage.

Unfortunately for Liffey, her ambition restoration dream home is the former abode of elderly Molly Tucker (Rita Tushingham), an eccentric neighbor who lives with her peculiar adult daughter Mabs (Miranda Richardson) – mother of three girls, but desperately wanting a son.

When Richard, an American, takes a trip back to his old haunts in NYC, Liffey learns she’s pregnant, which doesn’t sit at all well with Molly and Mabs. Certain that their family should be the ones to have a child, Molly and her brood, also occult dabblers, have no problem using black magic to upset Liffey’s pregnancy.

While certainly considered a minor work in Roeg’s canon, The Guardian’s Philip French accurately details the films as “a curious mixture of Straw Dogs and Rosemary’s Baby”, and if that descriptor piques your interest, be sure to see it.

11. Cold Heaven (1991)

Northern Irish-Canadian writer Brian Moore’s 1983 novel “Cold Heaven” is the source material for this supernatural-infused thriller from Roeg (adapted for the screen by Allan Scott).

Alex (Mark Harmon) and Marie Davenport (Theresa Russell) are an unhappily married couple in Mexico for a medical conference/working vacay, where Marie is gathering the nerve to tell Alex that they’re through and that she will be leaving him to be with her lover, Daniel (James Russo).

Inexplicably (at least at first) haunted by an image of the Virgin Mary, Marie takes her time before revealing her intentions to Alex, and before she’s able to confess her affair he is involved in a boat accident. The events of which are so horrific and contradictory, they seem buoyed by the hand of God. With the aid of Sister Martha (Talia Shire) and Father Niles (Will Patton), Marie will, hopefully, ascertain the truth. Was it a miracle or something else?

Narratively sewed up, technically impressive, and never specific to any one genre, it’s also a film that’s been described, not surprisingly, as challenging and polarizing (like pretty much all of Roeg’s work).

“Cold Heaven starts out as a standard melodrama about adultery, continues as a head-scratching mystery thriller, takes a slow left turn into religious allegory, and winds up as a speculative and highly moral poem about marriage,” wrote noted film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, adding; “Trying to squeeze this plot into a genre would almost constitute an act of violence against movie and audience alike.”

10. Track 29 (1988)

Another notable collaboration between Roeg and his then wife Theresa Russell is the somewhat scabrous Dennis Potter adaptation Track 29 –– itself a reworking of Potter’s 1974 television play, Schmoedipus. Relocating the action from London to North Carolina, Linda (Russell) is one day confronted by a young man named Martin (Gary Oldman), who claims to be her long-lost son.

Linda, deeply unhappy in her marriage to her ill-suited and unfaithful husband, Henry (Christopher Lloyd), she places her affections into Martin, whom she gave up for adoption years ago, when she was a desperate teenager. But a violent streak reveals itself in Martin, as does an unruly obsession Henry.

Track 29 deliberately confronts the viewer with kink, misogyny, and societal violence. It won’t sit well with its audience, nor is it supposed to. Tantalizing and perhaps tortuous, Track 29 will trouble you and turn in your mind for some time afterward, and that is the intent. In a conflicted and mixed review of the film Roger Ebert suggests that “…not every film is required to massage us with pleasure. Some are allowed to be abrasive and frustrating, to make us think.”

9. Castaway (1987)

Famously adapted from Lucy Irvine’s 1984 book “Castaway”, which detailed her year spent on the isolated isle of Tuin (nestled in the Torres Strait, between Australia and New Guinea) with writer Gerald Kingsland, this inspired true story, is also Roeg’s most conventional and therefore easy to digest, drama.

Amanda Donohoe is Lucy, a London secretary who answers an ad and beats out over 50 other applicants to join the wealthy and reclusive middle-aged writer, Gerald (Oliver Reed) on a tropical isle and be his wife for one year.

Par for the course with Roeg in the director’s chair, the visuals are nothing short of mesmeric (particularly the underwater sequences) and do the exotic locations considerable justice. Donohoe and Reed are excellent in their roles, and watching as their personalities coalesce and also crash, and how that resonated in their emotional and mental states is astonishing to behold.

Unfairly ignored on its initial release, Castaway was denied a U.S. release, it’s not just a film from an auteur director unfairly shunned, but a brilliant turn from a notable cast. “Reed gives the performance of his career as a sexually frustrated middle-aged man in search of sun and sex,” wrote Variety at the time of the film’s original release, also adding that “[Reed] is admirably complemented by Amanda Donohoe as the determined but fickle object of his lust.”

Thanks to an elegantly restored 4K Blu-ray and DVD editions, Castaway can and should be appreciated anew by admirers of Roeg’s. Don’t miss it.

8. Bad Timing (1980)

The scandalous, X-rated mini-epic Bad Timing (denounced unfairly as tasteless and misogynistic upon its original release) has been described by award-winning British author and cineaste Geoff Dyer “…as bonkers as it is beautiful”, and he’s not wrong.

Perhaps Roeg’s most polarizing film, it’s one that explores some very upsetting places as we get familiar with expat American psychiatrist Alex Linden (Art Garfunkel). Living in Vienna, and not a particularly likeable lad, Alex has a potentially dangerous, and certainly unhealthy sexual obsession with Milena (Theresa Russell), a married American woman with more than a few vices.

Also added to the jigsaw-puzzle-that’s-missing-a-few-pieces narrative is Harvey Keitel’s police inspector Netusil, a man convinced that Milena’s hospitalization isn’t as cut and dry as Alex has made it out to be, and this is illustrated via the detective’s fantasized replaying of what could have gone awry.

Told in Roeg’s atypical nonlinear fashion, Bad Timing may read as experimental arthouse inanity for non-fans or those not so adventurous. But Roeg takes pains to detail the voyeuristic psychoanalysis of a wronged relationship, as well as the wistful and lascivious elements of an affair; how despairing people still hold powerful passions, and how some actions are too horrible to be easily or ever forgiven.

7. The Witches (1990)

Ably assisted by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop (Henson was also a producer, and unfortunately he and Roeg regularly disagreed with one another during the production), and a wonderfully OTT Anjelica Huston, The Witches tells the tale of 9-year-old Luke Eveshim (Jasen Fisher), who is staying at a resort with his recuperating grandmother Helga in Norway (Mai Zetterling).

His idle is ruined by other guests at the hotel, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, led by one Miss Ernst (Huston) who also goes by the secret sobriquet of Grand High Witch. Luke is certain this society, secretly a witches coven, has a fondness for transforming children into mice.

The freakish fun of the Witches, which also zigzags into creepier waters at times, is also improved upon by Rowan Atkinson’s put upon hotel manager, Mr. Stringer. For inventive and ambitious fantasy for all ages, Roeg’s The Witches delivers. Perhaps the only real caveat here, and it’s one that ruffled Dahl’s feathers more than anyone else, is that it has a much more upbeat ending than the decidedly darker source material.

6. Insignificance (1985)

Adapted from Terry Johnson’s play, Roeg’s film occurs on a summer night in 1954, set in anonymous hotel rooms where the lives of four iconic figures; Marilyn Monroe (Theresa Russell), Albert Einstein (Michael Emil), Joe DiMaggio (Gary Busey) and Joe McCarthy (Tony Curtis) – though in the film they are simply and slyly referred to as the Actress, the Professor, the Ballplayer, and the Senator – fatefully intersect.

These recognizable popular culture figures, in typical Roeg fashion, riff on grandiose ideas and floundering emotions. What begins as trivial digressions gains momentum and significance, buoyed by stellar performances (like Curtis’s McCarthy, witch-hunting endlessly in his mind, or Russell’s Monroe, who, despite her ditzy dilettante routine can still teach Einstein a thing or two about relativity).

On the surface Insignificance may not be the exacting pedigree of Roeg’s recognized masterpieces, but it’s still a vast, ingenious allegory on fame, life, love, obsession, jealousy, and substantially so much more.

5. Eureka (1984)

Another of Roeg’s films to be unjustly ignored upon release, “Eureka was very bad timing,” he explains. “It was the early 1980s: Reagan and Thatcher were in, greed was good, and here was a film about the richest man in the world who still couldn’t be happy. Politically and sociologically, it was out of step.”

Inspired by compelling true events, Eureka tells the story of a Klondike prospector who hits it rich, the fictional Jack McCann (Gene Hackman), based off of Sir Harry Oakes, who was murdered in the Bahamas, on an island he owned back in 1943.

In Roeg’s film, Jack’s tale jumps back in forth through his life, and we find his dynasty from the gold rush put in jeopardy as his adult daughter Tracy (Theresa Russell) and her husband Claude (Rutger Hauer) scheme away to usurp his fortune, even his soul.

Simultaneously to this almost Shakespearean betrayal are a pair of greedy, mob-tied investors Mayakofsky (Joe Pesci) and Aurelio D’Amato (Mickey Rourke), but even they seem subdued compared to JAck’s own inner demons.

Director John Boorman (Deliverance [1972]) famously described Eureka as “the best picture ever made — for an hour”, and Danny Boyle (Trainspotting [1996]) recounted how inspiring he found the film; “There was a couple of scenes [in Eureka] in particular, a death scene, and a kind of orgy, and I remember I just felt completely breathless, just unable to catch a breath at all… It’s not a bad thing to aim for.”

As beautiful, bizarro, and byzantine as Roeg’s finest films, Eureka is a film in need of a reappraisal. “One of the richest movie labyrinths since Citizen Kane,” writes Film Comment’s Harlan Kennedy, and he’s not at all wrong. It’s another dizzying tour de force, and perhaps an unexpected one. “What Roeg brings to the party is a flair for the sensational,” enthused Roger Ebert, “for characters who are larger than their weaknesses, who are connected to great archetypal forces.”

4. Performance (1970)

Roeg’s directorial debut (co-directed with Donald Cammell) was a product of the psychedelic and very Swinging Sixties. Produced in ‘68, Performance didn’t get released until 1970 as Warner Brothers was cold footed to release a film with such graphic violence and strong sexual content.

Today viewed as the quintessential cult film, Performance is all hallucinations and psychologically complex melodramatics, geniusly shot and edited into a compelling and complex mosaic.

Also contained within its paranoia-addled mainframe is a zero cool British gangster template (a huge influence on the crime films of Guy Ritchie and Quentin Tarantino, amongst others), and one of the most influential and imitated soundtracks of that era (Ry Cooder’s slide guitar gets mad props).

The film stars James Fox as a violent, hair-trigger hitman from London named Chas. In a serious jam, Chas tracks down the semi-reclusive rock star Turner (Mick Jagger, in his film-acting debut), looking for a place to hideout.

Turner lives with two smokin’ hot scenester companions, Pherber (Anita Pallenberg) and Lucy (Michele Breton), and though Chas and Turner initially clash, their mutual fascination with one another, combined with their drug-enhanced psychological sparring results in a stunning blur of assimilation, self-loss, and identity thievary. Sensational strangeness abounds in this phenomenal mindfuck of a film.

3. Walkabout (1971)

“A meditation about living on earth, which finds beauty in the way mankind’s intelligence can adapt to harsh conditions while civilization just tries to wall them off or pave them over,” praised Roger Ebert, who wrote about the film many times, accurately and enthusiastically proclaiming that “Walkabout is one of the great films.”

Powerful visual compositions with an almost religious intensity permeates Roeg’s meditative, haunting, and at times eerily surreal story of survival in the Australian outback. Using James Vance Marshall’s 1959 novel “The Children” as a starting point, Roeg’s story involves a teenage girl (Jenny Agutter) and her little brother (Luc Roeg, the director’s son), who are left stranded in the wild after their father (John Meillon) suffers a breakdown and attempts to murder them before his own horrific suicide.

Aided by an Aboriginal boy (David Gulpilil) on his titular rite of passage journey, and Roeg’s exuberant visual dynamism, Walkabout is an exotic, inspiring, and absolutely unforgettable arthouse entry.

“One of the most original and provocative films of the 1970s,” wrote The Movie Guide’s James Monaco, adding that “Walkabout is set in terrain stranger and more awe-inspiring than that of any science fiction film.”

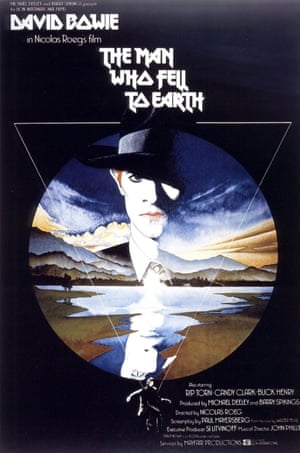

2. The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

With an abundance of unexplained skips in location and chronology and his cheeky trademark sophisticated style, Roeg’s adaptation of the 1963 Walter Tevis novel, “The Man Who Fell to Earth” is an ambitious and meditative marvel that was, of course, quite ahead of its time.Described by Time Out as “the most intellectually provocative genre film of the 1970s,” and starring Thin White Duke-era rock icon David Bowie as Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien who’s doomed visit to Earth offers up a multifaceted and ultra-sophisticated inspection of American culture, heartbreak, and homesickness.

The film struck a chord with niche audiences, rendering it cult status pretty quickly (prolific sci-fi author Philip K. Dick became particularly smitten with the film, incorporating elements of it and of Bowie’s iconic eminence into his must-read 1981 masterpiece “VALIS”).

Bowie’s character is named for the English scientist Isaac Newton, discoverer of gravity, and as our protagonist in this mind-bending SF masterpiece, he makes discoveries as philosophically and psychologically substantial.

“The story unfolds in a daring sequence of narrative leaps,” writes The Guardian film critic Peter Bradshaw in his glowing five star review, adding that the film is “a freaky, compelling concept album of a film.”

Poignant, provocative, and deeply transfixing, genre films are rarely as meaningful, extravagant, or as ambitious as The Man Who Fell to Earth. Populist cinema this most certainly is not (when was Roeg, wearing his director’s hat, ever mainstream?), and though at times perhaps indecipherable, Roeg is a satirist and an artist of incredible breadth of view. When was sci-fi ever this iconoclastic and cool?

1. Don’t Look Now (1973)

“[Don’t Look Now] remains one of the great horror masterpieces, working not with fright, which is easy, but with dread, grief and apprehension,”

writes Roger Ebert, adding that “few films so successfully put us inside the mind of a man who is trying to reason his way free from mounting terror.

Roeg and his editor, Graeme Clifford, cut from one unsettling image to another. The movie is fragmented in its visual style, accumulating images that add up to a final bloody moment of truth.”

After their daughter’s tragic death by drowning, grieving parents John and Laura (Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie) retreat to Venice in hopes of healing and finding peace in Roeg’s stunning arthouse horror Don’t Look Now, itself a very inspired and embellished adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s 1971 short story.

Using a fragmented visual style involving abrupt cuts, unanticipated segues, ambiguous, often cryptic associations (the color red has never been so unsettling), Roeg creates a feeling of perpetual dread and impending doom.

This suffocating atmosphere that Roeg so expertly conjures is met with an unforgettable romantic interlude wherein John and Laura make love in one of the most brazenly erotic scenes in all of cinema. Controversial back in 1973, the love scene is still shocking and miraculous when viewed today, 45 years later.

Prolonged, explicit, and imitated many times since (perhaps most notably in Steven Soderbergh’s Out of Sight [1998]) the passion of the damaged couple is unmistakable, and their pre- and post-coital embrace of one another shows a passion and an affinity that feels absolutely genuine.

“[Don’t Look Now] is an example of high-fashion Gothic sensibility,”

wrote Pauline Kael, remarking how

“Venice, the labyrinthine city of pleasure, with its crumbling, leering gargoyles, is obscurely, frighteningly sensual here, and an early sex sequence with Christie and Sutherland nude in bed, intercut with their post-coital mood as they dress to go out together, has an extraordinary erotic glitter. Dressing is splintered and sensualized, like fear and death… Roeg comes closer to getting Borges on the screen than those who have tried it directly.”

Wow!

In the years since its release Don’t Look Now is regularly regarded as one of the greatest British films of all time (a recent 2011 panel of industry experts organized by Time Out ranked it number one), often echoing sentiments articulated by the San Francisco Chronicle calling it “a haunting, beautiful labyrinth that gets inside your bones and stays there.”

Don’t Look Now is a troubling, stunning, and sensual masterpiece you’ll never forget, and it’s also the pièce de résistance of a major filmmaker at the height of his considerable powers.

Author Bio:Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx.Follow Shane on Twitter@ShaneScottravis

David Bowie, John Phillips, and the missing soundtrack: the amazing story behind The Man Who Fell to Earth - screaming maids, boozy brawls, and cocaine hallucinations

Bowie and the missing soundtrack: the amazing story behind The Man Who Fell to Earth

David Bowie is rumored to have written a score to the sci-fi classic that’s locked up in some vault. But the truth is much stranger – involving screaming maids, boozy brawls and coke-induced hearing hallucinations

David Bowie with Nicolas Roeg on the set of The Man Who Fell to Earth in 1975. Photograph: Duffy/Getty Images

There is a great mystery at the heart of The Man Who Fell to Earth, Nicolas Roeg’s cult film: its soundtrack. There is a persistent rumour that long-lost music for the film – recorded by its star David Bowie – sits somewhere in a vault. There’s only one problem: Bowie’s soundtrack to The Man Who Fell to Earth doesn’t actually exist.

The music that appears in the film – released for the first time next month as part of a collector’s edition by Studio Canal and a vinyl box set by Universal – was written and produced by John Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas.

The never-before-told story of its creation is almost as improbable as Roeg’s film. Signed to both star in and compose an original soundtrack for the film, Bowie, then at the peak of his early fame, intended to record the music once shooting had completed, envisioning it as the follow-up to his album Young Americans. But he began working instead on Station to Station, while deep into his cocaine and milk phase. After three months, he had managed to complete only five or six tracks in a bizarre mishmash of styles – from country rock to instrumentals on African thumb pianos and atonal electronic music.

The British arranger Paul Buckmaster worked on the demos with Bowie at his rented house in Bel Air, and at Cherokee Studios in Hollywood. Although they had composed the music playing along to a videotape of the film, none of it was actually synched to the picture, rendering it almost unusable. “I think [Roeg] just got these disparate pieces and probably said, ‘What the hell is this?’” says Buckmaster.

Finding himself without a soundtrack weeks from the film’s planned premiere in March 1976, Roeg turned to the Mamas and Papas songwriter. Phillips’ third wife, Genevieve Waite (a South African actor and model), had introduced him to Roeg in 1970, when the director was in LA to work on Performance.

Four years later, the director came to see Phillips and Waite performing a musical-comedy double act at Reno Sweeney cabaret club in Greenwich Village. Afterwards, he offered Waite the role of Mary Lou in The Man Who Fell to Earth opposite Bowie – the role that eventually went to Candy Clark. “He told John he wanted me to do it,” she says. But Phillips had other ideas. He had written his own sci-fi themed rock musical for his wife to star in, called Space, which was about to go into production. “John said, ‘Genevieve’s going to be working on the Broadway show.’ And he and Nic Roeg were so drunk they had this terrible fight and knocked over tables and stuff.”

“Those kind of episodes with Nic were relatively … I wouldn’t say frequent but they were not infrequent,” says Graeme Clifford, who edited The Man Who Fell to Earth. “Everybody who knows Nic, at one point or another, has got into a rolling around on the floor fight with him. If John Phillips had not had a fight with him, I’d say, ‘Oh really?’”

The next time the pair met, Phillips was living in Malibu.

“We went to Candy Clark’s house,” he said in an interview before his death in 2001. “Nic was going with her at the time.” Roeg showed him a cut of the film on a small portable TV. “I just loved the movie the moment I saw it.” He was unsure why Roeg was asking him to work on the soundtrack when Bowie was the obvious choice, but took the job anyway, aiming to create a “real American score with banjos and folk and rock”.

Phillips – whose career started in the late 1950s in a doo-wop/jazz vocal group called the Smoothies, before he founded, first, folk trio the Journeymen, then the Mamas and the Papas – was steeped in American roots music. A musical chameleon like Bowie, he had moved effortlessly through a succession of styles, with a marked virtuosity, and had previously worked on soundtracks for Myra Breckinridge and Robert Altman’s Brewster McCloud.

On arriving in London in 1976, faced with putting together a score from scratch in an exceedingly short time, Phillips knew he needed “someone who could really play”. That person was Mick Taylor, erstwhile guitarist for the Rolling Stones, who he considered “the best guitar player in the world”.

They started work at Glebe Place, Phillips’ rented house in Chelsea. One day, Phillips recalled, “Keith Richards walked in and there’s Mick Taylor sitting there. We’re playing guitar together.” On seeing Taylor, Richards let out a scream. “They both froze.” They hadn’t seen each other since Taylor had walked out on the Stones just over a year earlier. “It was a little testy,” Phillips said.

Richards and Taylor behaved “like dogs circling”. Keith broke the ice the only way he knew how: he grabbed a guitar and joined in. “We just played old country songs,” Phillips said. Those would become the basis for the music Phillips recorded for the film, which included originals like LISTEN Boys from the South, as well as spirited covers of Hank Snow’s WATCH Rhumba Boogie and Bill Monroe and his Bluegrass Boys’ WATCH Bluegrass Breakdown.

“Some of the music was very improvised,” says Richard Goldblatt, one of the engineers who worked with Phillips. “The recordings were quite innovative.” Despite being under immense pressure to produce the music in a matter of weeks, Phillips continued to lead a busy and complicated life of narcotic and sexual excess. After one session, he arrived back home around two in the morning. Finding nobody there, he walked round to his friend Mick Jagger’s house on Cheyne Walk, looking for his wife. Instead, he found Bianca Jagger and Liza Minnelli’s younger sister, Lorna Luft. Genevieve wasn’t there and nor was Mick. “We all sat around, drank wine and got pissed,” said Phillips. “I was playing the guitar, singing some songs and stuff.” Eventually, Luft left and John and Bianca – who had enjoyed a brief affair in 1970, before she met and married Jagger – ended up in bed.

At some point close to dawn, they both fell asleep. At the session the following morning, Phillips was a no-show. The musicians and engineers all sat waiting. Someone rang Glebe Place to find out where he was. Waite took the call. She went round to Cheyne Walk, figuring he might be there, talked the help into letting her in and was told he was in the bedroom – with Bianca.

“So we were awakened around 10.30am,” Phillips said. “There was Genevieve, ‘I know you’re in there, you two.’ Oh God, here I am in Mick’s bed with Mick’s old lady. My old lady’s outside, banging on the door. There were Nicaraguan maids running around, screaming in Nicaraguan.

Genevieve storms in the door and takes a swing at Bianca. I sort of hold Genevieve back and take her out. She just ran down the street. I had to go to work.”

The final session for the score took place in February, with the film’s world premiere at Leicester Square in London now just three weeks away. Phillips began to mix the tracks so they could be laid into the edit. At that point, says Goldblatt, “suddenly, he started to go a little peculiar”.

He could hear clicks and noises on the tape and, despite the engineer’s insistence that there was nothing there, insisted they do everything over. But the problem persisted. By the fourth or fifth day, things were pretty tense between them. Then something snapped. “He lost it for some reason,” says Goldblatt, who walked out of the session and returned the next morning to find he’d been replaced by another engineer.

Goldblatt was later told that “the projectionist had gone into the toilets and all he could hear was somebody in the cubicle next to him sniffing – big sniffs”. The bathroom breaks Phillips had been taking, almost at the end of every take, suddenly made sense. “He was doing unbelievable amounts of coke.” So much, Goldblatt believes, that he was having auditory hallucinations. Rafe McKenna, assistant engineer, recalls Roeg coming to the studio to have a “serious discussion with Phillips about his behaviour. Told him off, basically, and said stop pissing off the engineers and get it finished tonight.”

The eleventh hour entreaty worked. “The music just came flying out of the studio and I stuck it in,” says editor Graeme Clifford. Roeg declares himself happy with the music Phillips produced for the film. “It had a range of different qualities that I thought was rather interesting,” he says. “He really was an individual composer.”

• The restored The Man Who Fell to Earth is in UK cinemas on 9 September, when the soundtrack will also be available, and then on DVD and Blu-ray on 24 October.

June 22, 2018

#LindaGailLewis @rxgau (Robert Christgau) Review A- International Affair [New Rose, 1991] #thanks — @mrjyn (producer)

(the producer)

#LindaGailLewis

International Affair [New Rose, 1991]

The long-ago costar of the lowbrow gem Together registers more twang per syllable than prime Duane Eddy, belting and screeching like a flat-out hillbilly--Jeannie C. Riley

— mrjyn (@mrjyn) June 23, 2018

June 21, 2018

oUtSIDer aRT tAGs

African-American Apocalyptic Architecture Art and Disability Autism Burning Man Chand Chicago Classics Collage Collections Corbaz Cover Articles Death Definitions and Debate Dial Drawing Environments Fantastic Finster Gugging Healing Institutionalised Inventions Jamaica Le Derner Cri Living Artists Mediumistic Miniatures Mosaic Music Naîve New Orleans New York Obsession Occult Organizations Painting Performance Photography Prison Art Prophets Psychedelic Punk Rastafari Religious Religious Art Schizophrenia Sculpture Southern Street Art Surrealism Textiles UFOs Urban Art Vernacular Visionary War Wolfli Woman Artists

Hellbent Guitars For Leather (Must've taken Marcus Ohara days to compile - go see his blog)

Guitars With Leather Covering

Elvis admitted he knew 3 chords on the guitar. For him the guitar was a stage prop; something to hold on to and make him look cool. And what could make the guitar look cooler? A hand-tooled leather cover with Elvis' name embossed on!

So from the late 1950’s on there have been guitarists that have covered their instruments in leather. It was all about stage presence and show.

Elvis had several guitars wrapped in leather. His first was a 1955 Martin D-28 that he purchased at O.K. Houck Piano Company in Memphis Tennessee in April of 1956.

The leather tooled covering was made by Marcus Van Story, who worked for the O.K. Houck Piano Company as a repairman.

Presley got the idea because he admired a similar guitar cover used by Hank Snow and decided he needed one. I do not know where Hank Snow got his, but it was elaborate and had his name engraved across its top.

Snow got the idea for this when he came to the attenion of Country artist, Ernest Tubb. Tubb had the word “Thanks” written on the back of his guitars. It was written upside-down, so when the audience applauded, he turned the guitar over as a way to show appreciation.

Other Country artists had their names inlaid in mother-of-pearl on their guitars fret boards. However the leather guitar cover was a real eye-catcher, despite the fact that it probably muffled the sound.

In October of 1956, Presley purchased a brand new Gibson J-200 from the same music store.

This was covered with a tooled leather cover made by Charles Underwood in 1957. It was first seen on the Ed Sullivan Show that same year.

Buddy Holly first saw Elvis at Fair Park Coliseum in Lubbock, Texas in 1955. Holly took a shine to Elvis’ fancy leather guitar cover and had one made by Rick Turner, who was working at Westwood Music in Los Angeles.

Rick Turner with Holly's guitar

Years later Gary Busey, who starred in The Buddy Holly Story purchased Buddy’s Gibson J-45, with the leather cover for $270,000. Rick Turner has also made beautiful replicas of this same leather guitar cover.

Conway Twitty was born Harold Lloyd Jenkins. When he decided to go into music he did not think his real name did not have star qualities. He looked through a map and found two cities that appealed to him, Conway Arkansas and Twitty Texas to come up with his stage name.

Twitty already owned and played electric guitar which was a 1957 Gretsch 6130 Roundup solid body electric guitar. This guitar came from the factory with leather binding on the instruments sides that were embossed with medallions that looked like sheriff badges.

But Twitty decided to have a hand-tooled leather guitar cover custom made for his Gretsch guitar. His name is embossed in cursive script on the upper bouts.

On the back of the guitar is a architecture of his wife, Maxine, who he called “Mick. She is embossed on the covers back and is shown wearing chaps and a cowboy hat.

Another popular artists of those day was Ricky Nelson. If you grew up in the 1950’s, you probably watched the television show, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. Ricks father, Ozzie led an orchestra in the 1940’s and was the bands singer. His mother, Harriet was the bands female vocalist.

So it was not surprising that Ricky developed a beautiful singing voice. I discover that while he was at a recording session he heard a session guitarist that was about his same age named James Burton. Burton was recording in another studio.

Rick liked his style and invited him to be not just a regular in his band, but also appear on the TV show.

At the time Rick owned a Rickenbacker acoustic guitar that was about the same size as a Gibson jumbo guitar.

He had a beautiful leather guitar cover for this guitar and of course it had his name engraved in the leather.

As Nelson became more famous, he purchased a Gibson J-200 and had a leather cover made for it.

Later in his career Ricky purchased a Martin guitar and he had a custom leather cover with his name made for this instrument. Judging be the rosewood neck, it is a Martin D-18.

He also received a red, white and blue guitar as a gift from Buck Owens.

Buck thoughtfully included a leather cover.

The leather cover fad seemed to have fallen out of fashion until a clean-cut Waylon Jennings, took his Fender Broadcaster to a leather-smith and had a black and white hand-tooled leather cover made for the instrument. This guitar became Jennings trademark.

Shortly afterward he purchased two Fender Telecasters and gave them the same treatment. It is said that Jennings owned at least 7 Fender Telecasters with leather coverings, although one was actually an Esquire.

Jennings gave away the Broadcaster to a friend. Seven years after his death, this guitar showed up in an auction in 2009 at Christies and was purchased for $98,500.

Fender Musical Instruments made a Waylon Jennings Telecaster Tribute guitar during his lifetime. They had his stylized “W” logo at the 12th fret on their maple necks. Jennings owned several of these guitars.

His son, Shooter Jennings, plays his fathers Telecaster with his own band.

During the late 1980’s Chris Isaak’s became popular. He was a singer and songwriter, but before this he earned a living as a male fashion model.

Isaak's song Suspicion of Love appeared in the film, Married to the Mob. In 1990 his song Wicked Game was featured in the David Lynch film, Wild at Heart. A VH1 music video featured Isaak and supermodel Helen Christensen in a sensual beach encounter.

In 2001 Isaak starred in his own television variety show. During his stage act, Isaak wore flashy suit jackets with medallions on the lapels.

And though his first stage guitar was a black Silvertone 1446 model, he is best known for his Gretsch Country Gentleman with the leather hand-tooled cover, that he played during the height of his popularity.

In later years he acquired a Gibson Chet Atkins Country Gentleman and enclosed that instrument in a leather cover.

There are a number of artisans throughout the United States that will provide leather guitar covers.

Guitars N' Things in Nashville, Tennessee offers reasonable prices on hand-tooled leather covers.

Mosby Guitars and Custom Inlay is located in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina and does custom leather hand-tooling work.

For those who are adventurous, I've found this site with step-by step instructions.

Here are a few examples of folks that have done their own work with great results.

This is a leather guitar cover made for a Martin Eric Clapton model.

And this beautiful example if a Gibson ES-345 covered in leather.

Posted by

marcus ohara

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)