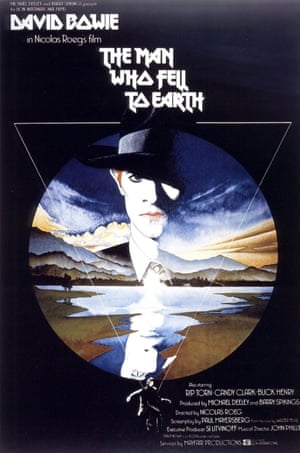

Bowie and the missing soundtrack: the amazing story behind The Man Who Fell to Earth

David Bowie is rumored to have written a score to the sci-fi classic that’s locked up in some vault. But the truth is much stranger – involving screaming maids, boozy brawls and coke-induced hearing hallucinations

David Bowie with Nicolas Roeg on the set of The Man Who Fell to Earth in 1975. Photograph: Duffy/Getty Images

There is a great mystery at the heart of The Man Who Fell to Earth, Nicolas Roeg’s cult film: its soundtrack. There is a persistent rumour that long-lost music for the film – recorded by its star David Bowie – sits somewhere in a vault. There’s only one problem: Bowie’s soundtrack to The Man Who Fell to Earth doesn’t actually exist.

The music that appears in the film – released for the first time next month as part of a collector’s edition by Studio Canal and a vinyl box set by Universal – was written and produced by John Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas.

The never-before-told story of its creation is almost as improbable as Roeg’s film. Signed to both star in and compose an original soundtrack for the film, Bowie, then at the peak of his early fame, intended to record the music once shooting had completed, envisioning it as the follow-up to his album Young Americans. But he began working instead on Station to Station, while deep into his cocaine and milk phase. After three months, he had managed to complete only five or six tracks in a bizarre mishmash of styles – from country rock to instrumentals on African thumb pianos and atonal electronic music.

The British arranger Paul Buckmaster worked on the demos with Bowie at his rented house in Bel Air, and at Cherokee Studios in Hollywood. Although they had composed the music playing along to a videotape of the film, none of it was actually synched to the picture, rendering it almost unusable. “I think [Roeg] just got these disparate pieces and probably said, ‘What the hell is this?’” says Buckmaster.

Finding himself without a soundtrack weeks from the film’s planned premiere in March 1976, Roeg turned to the Mamas and Papas songwriter. Phillips’ third wife, Genevieve Waite (a South African actor and model), had introduced him to Roeg in 1970, when the director was in LA to work on Performance.

Four years later, the director came to see Phillips and Waite performing a musical-comedy double act at Reno Sweeney cabaret club in Greenwich Village. Afterwards, he offered Waite the role of Mary Lou in The Man Who Fell to Earth opposite Bowie – the role that eventually went to Candy Clark. “He told John he wanted me to do it,” she says. But Phillips had other ideas. He had written his own sci-fi themed rock musical for his wife to star in, called Space, which was about to go into production. “John said, ‘Genevieve’s going to be working on the Broadway show.’ And he and Nic Roeg were so drunk they had this terrible fight and knocked over tables and stuff.”

“Those kind of episodes with Nic were relatively … I wouldn’t say frequent but they were not infrequent,” says Graeme Clifford, who edited The Man Who Fell to Earth. “Everybody who knows Nic, at one point or another, has got into a rolling around on the floor fight with him. If John Phillips had not had a fight with him, I’d say, ‘Oh really?’”

The next time the pair met, Phillips was living in Malibu.

“We went to Candy Clark’s house,” he said in an interview before his death in 2001. “Nic was going with her at the time.” Roeg showed him a cut of the film on a small portable TV. “I just loved the movie the moment I saw it.” He was unsure why Roeg was asking him to work on the soundtrack when Bowie was the obvious choice, but took the job anyway, aiming to create a “real American score with banjos and folk and rock”.

Phillips – whose career started in the late 1950s in a doo-wop/jazz vocal group called the Smoothies, before he founded, first, folk trio the Journeymen, then the Mamas and the Papas – was steeped in American roots music. A musical chameleon like Bowie, he had moved effortlessly through a succession of styles, with a marked virtuosity, and had previously worked on soundtracks for Myra Breckinridge and Robert Altman’s Brewster McCloud.

On arriving in London in 1976, faced with putting together a score from scratch in an exceedingly short time, Phillips knew he needed “someone who could really play”. That person was Mick Taylor, erstwhile guitarist for the Rolling Stones, who he considered “the best guitar player in the world”.

They started work at Glebe Place, Phillips’ rented house in Chelsea. One day, Phillips recalled, “Keith Richards walked in and there’s Mick Taylor sitting there. We’re playing guitar together.” On seeing Taylor, Richards let out a scream. “They both froze.” They hadn’t seen each other since Taylor had walked out on the Stones just over a year earlier. “It was a little testy,” Phillips said.

Richards and Taylor behaved “like dogs circling”. Keith broke the ice the only way he knew how: he grabbed a guitar and joined in. “We just played old country songs,” Phillips said. Those would become the basis for the music Phillips recorded for the film, which included originals like LISTEN Boys from the South, as well as spirited covers of Hank Snow’s WATCH Rhumba Boogie and Bill Monroe and his Bluegrass Boys’ WATCH Bluegrass Breakdown.

“Some of the music was very improvised,” says Richard Goldblatt, one of the engineers who worked with Phillips. “The recordings were quite innovative.” Despite being under immense pressure to produce the music in a matter of weeks, Phillips continued to lead a busy and complicated life of narcotic and sexual excess. After one session, he arrived back home around two in the morning. Finding nobody there, he walked round to his friend Mick Jagger’s house on Cheyne Walk, looking for his wife. Instead, he found Bianca Jagger and Liza Minnelli’s younger sister, Lorna Luft. Genevieve wasn’t there and nor was Mick. “We all sat around, drank wine and got pissed,” said Phillips. “I was playing the guitar, singing some songs and stuff.” Eventually, Luft left and John and Bianca – who had enjoyed a brief affair in 1970, before she met and married Jagger – ended up in bed.

At some point close to dawn, they both fell asleep. At the session the following morning, Phillips was a no-show. The musicians and engineers all sat waiting. Someone rang Glebe Place to find out where he was. Waite took the call. She went round to Cheyne Walk, figuring he might be there, talked the help into letting her in and was told he was in the bedroom – with Bianca.

“So we were awakened around 10.30am,” Phillips said. “There was Genevieve, ‘I know you’re in there, you two.’ Oh God, here I am in Mick’s bed with Mick’s old lady. My old lady’s outside, banging on the door. There were Nicaraguan maids running around, screaming in Nicaraguan.

Genevieve storms in the door and takes a swing at Bianca. I sort of hold Genevieve back and take her out. She just ran down the street. I had to go to work.”

The final session for the score took place in February, with the film’s world premiere at Leicester Square in London now just three weeks away. Phillips began to mix the tracks so they could be laid into the edit. At that point, says Goldblatt, “suddenly, he started to go a little peculiar”.

He could hear clicks and noises on the tape and, despite the engineer’s insistence that there was nothing there, insisted they do everything over. But the problem persisted. By the fourth or fifth day, things were pretty tense between them. Then something snapped. “He lost it for some reason,” says Goldblatt, who walked out of the session and returned the next morning to find he’d been replaced by another engineer.

Goldblatt was later told that “the projectionist had gone into the toilets and all he could hear was somebody in the cubicle next to him sniffing – big sniffs”. The bathroom breaks Phillips had been taking, almost at the end of every take, suddenly made sense. “He was doing unbelievable amounts of coke.” So much, Goldblatt believes, that he was having auditory hallucinations. Rafe McKenna, assistant engineer, recalls Roeg coming to the studio to have a “serious discussion with Phillips about his behaviour. Told him off, basically, and said stop pissing off the engineers and get it finished tonight.”

The eleventh hour entreaty worked. “The music just came flying out of the studio and I stuck it in,” says editor Graeme Clifford. Roeg declares himself happy with the music Phillips produced for the film. “It had a range of different qualities that I thought was rather interesting,” he says. “He really was an individual composer.”

• The restored The Man Who Fell to Earth is in UK cinemas on 9 September, when the soundtrack will also be available, and then on DVD and Blu-ray on 24 October.