A Tribute to Jazz Historian Al Rose

“I suggest that the city cannot afford a cultural fiasco that will make it a laughing stock at best … Far better to have no jazz festival than a fake jazz festival.”

In August 1967, a particularly sharp-tongued letter ran in the New Orleans Times-Picayune.

“… I suggest that the city cannot afford a cultural fiasco that will make it a laughing stock at best,” it read. “… Far better to have no jazz festival than a fake jazz festival.”

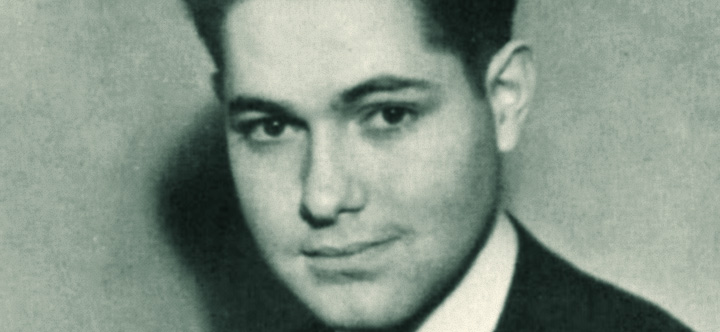

The writer was Al Rose, a notoriously opinionated New Orleans native, a pioneering jazz producer and historian, writer, artist, and adventurer. Rose, born Etienne Alfonse de la Rose Lascaux died on December 15, 1993, due to complications from a stroke. He was 77.

But what was Rose’s beef with the event that would become known as “Jazzfest”?

Well, apparently #NOLA has been able to afford it - it is laughably mostly not jazz (what little there is has been shunted to side stages in poor time slots in order to maintain a fig leaf of jazz cred), and yet people still go and pay..their URL tells it: https://t.co/PlOz93X5cL https://t.co/FvzBtWLcXR— Theo Pando Ra (@theopandora) January 6, 2019

The organizers, it seemed, had announced plans to bring performers Stan Kenton, Duke Ellington, and Count Basie to the city musicians that Rose did not consider true jazz artists.No, he argued, this was orchestra music, “rooted in European forms and “…not related to, not derived from, not evolved from jazz in any way.” To be jazz, as Rose wrote in the preface to his reference work New Orleans Jazz: A Family Album, “music must be (a) improvised, (b) be played in 2/4 or 4/4 time, and (c) retain a clearly definable melodic line.”

There is only one type of jazz, wrote Rose to the Times-Picayune. You don’t think so? Come on, debate me. The festival went on, however. And Rose went back to work. Championing authenticity in jazz was Rose’s lifelong mission.

“He had a personal attitude towards himself and the world,” says fellow jazz historian and musician Danny Barker, a close friend. “He was a man you couldn’t argue with—you could not change his mind on nothing. He’d go down fighting.”

And like a jazz cat with nine lives, Rose spent his life fighting for ideas. His battles were waged on many fronts: music, art, politics. This included a stint in Mexico as bodyguard for exiled Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. And, reputedly, Rose also spent some time smuggling guns during the Spanish Civil War, parachuting into Spain to free political prisoners and smuggling revolutionaries into this country in a boat with a false bottom.

“I’m still finding bullet holes and scars on Al that I’d never seen before,” his wife, Diana Rose, once told me.

I met Al and Diana just five months ago, when I hoped to write a profile for Louisiana Cultural Vistas of Al’s curious life. I had heard all the stories, and wanted to meet this Hemingwayesque character who lived in my city, and who offered a window to the secret courtyards of the 20th century.

Al Rose, at the microphone, poses with (from left) Earl Hines, Louis Armstong, Barney Bigard and Arvel Shaw at Philadelphia’s Academy of Music in 1947.

Sadly—for me, at least—that story will not be completed. Rose welcomed conversation, but his mysteries were now impenetrably closeted in his mind. Perhaps searching for a “Rosebud” during our only interview, I asked him if there was one thing he had learned that held true, whether he was working in jazz, art, or politics. He had a quick answer.

“People always resisted the idea of having an idea,” he said.

Rose started acting on his ideas early. At 14, he ran away from home after refusing to be confirmed into the Catholic church, reputedly writing on the bathroom mirror, “Don’t try to find me.” He changed his name and made his living drawing caricatures in Mobile, Alabama, and New York’s Coney Island, and invented a false past and enrolled in a prep school in Pennsylvania.

Rose had been exposed to jazz as a child, when his father hired a band for a traveling carnival, and musicians often served as his babysitters. In 1936, when he was 19, Rose produced what was the first jazz concert, in Philadelphia. For the first time ever, people bought tickets and sat in chairs and treated jazz as seriously as European classical music. The program that first night included Sidney Bechet, Sidney De Paris, and Freddie “Gatemouth” Moore.

Then Rose left for Mexico, where he studied art with the famous muralist, Diego Rivera. He lived with Rivera and, as part of his tuition, he protected Trotsky. “I had the conviction that he was doing important work,” he once said, adding that he wasn’t actually a Trotskyite. ‘There were 12 separate incidents in which we were fired on. I had a tooth shot out. And I had to use a variety of names. I was only 22.”

Returning to the United States, Rose worked as a welder in Philadelphia and helped organize the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). He produced countless jazz concerts and over a hundred records, and in 1946 he launched a syndicated radio program, Journeys into Jazz.

“The secret to my life is it doesn’t click,” he once said. “It’s not pointless, but aimless.” Rose met Diana, his third wife, at a Mensa meeting in Florida. She takes some credit for steering him into his late career as a writer. “I wanted him to start doing something that wasn’t so dangerous,” she explained.

New Orleans Jazz: A Family Album was Rose’s first book, which he published in 1967 with Edmond Souchon. Then came Storyville, New Orleans, which includes seven reminiscences by madams and prostitutes who worked in the infamous red-light district. One of these interviews became the basis for the Louis Malle film, Pretty Baby. But when Rose realized that the film was going to be historically inaccurate, he tried to return his money and begged that his name be stricken from the credits. He failed; his name remains at the end of the film.

One of Rose’s best friends was ragtime pianist Eubie Blake, and Rose published a biography of him in 1979. In his forward to the book, Blake himself wrote that “When I first read the manuscript, I learned a lot about Eubie Blake …” But it’s I Remember Jazz: Six Decades Among the Great Jazzmen, published in 1987, that reveals the most about Rose himself. It chronicles his own aimless, but never pointless journeys into jazz, 60 years of friendships and behind-the-scenes work with the music he so fiercely defined and defended.

Although Rose once said that he had “no fierce need for immortality,” his work shows no sign of slowing down. His collection of band arrangements, photographs, books, sheet music, correspondence, and recordings is a major attraction of the Hogan Jazz Archives at Tulane, and has been used in hundreds of doctoral dissertations. One of his books, a biography of Storyville madam Lulu White, has only so far been published in France. And a documentary team is currently producing a study of Storyville, using filmed interviews with Barker and Rose.

According to Diana Rose, her husband was physically incapable of raising his voice past conversational tones. But when he stood up at age 14 to deliver his lifelong solo, he blew loud and hard. Sure, Jazzfest organizers, Pretty Baby, and Trotsky’s assassins all eventually found their mark.

But in jazz, that great musical forum for the exchange of ideas, so did Al Rose.

Michael Tisserand is a New Orleans-based freelance writer. A graduate of the University of Minnesota, his work has appeared in Offbeat magazine, Downbeat and USA Today. He is the author of The Kingdom of Zydeco (1998) and Sugarcane Academy: How A New Orleans Teacher and His Storm-Struck Students Created a School to Remember (2007).