Continuity of care refers to the continuous flow of care in a timely and appropriate manner.

Continuity includes: • Linkages between primary and specialty care; • Coordination among specialists; • Appropriate combinations of prescribed medications; • Coordinated use of ancillary services; • Appropriate discharge planning; and • Timely placement at different levels of care including hospital, skilled nursing and home health care.

If providers do not want to continue accepting Medicaid from an existing patient, can they stop seeing the patient? If a provider does not want to continue accepting Medicaid/Bayou Health plan from an existing patient, they must notify the recipient before they want to stop seeing the patient.

The patient can either continue seeing the provider as a private pay patient or they may find another provider to accept their Medicaid/Bayou Health plan card.

You must notify the recipient first and give them ample time to find another provider that will accept their Medicaid/Bayou Health plan card.

Ample time is considered at least two (2) months prior to discontinuing services.

EPSDT providers must call the EPSDT contractor to have that recipient unlinked from their caseload.

Louisiana Behavioral Health Advisory Council History of Mental Health Planning and Advisory Councils With Public Law 102-321, passed in 1992, the federal government dictated mental health planning as a condition of receipt of federal mental health grant funds, and has mandated participation in the planning process by stakeholder groups, including mental health consumers, parents of children with serious emotional or behavioral disturbances and family members.

The Louisiana Behavioral Health Advisory Council is Louisiana's planning organization.

ETHICS COMMENTARY

psychiatry online.org

Common types of anxiety seen in psychiatric practicea Anxiety type Examples Anxiety illness due to another medical condition Thyroid disease, pheochromocytoma

Personality trait Anxious, avoidant, dependent Mood illness related Unipolar depression, bipolar illness Psychotic illness related Schizophrenia, depression with psychotic features Primary anxiety illness Posttraumatic stress disorder, specific phobia Existential anxiety Fear of death and impermanence

in the midst of a global pandemic.

Symptoms of anxiety and depression have increased con- siderably since the COVID-19 pandemic began (5).

Many people are experiencing unprecedented levels of loss, grief, and constraints in life—and bearing it all while feeling more alone and isolated than ever before.

We would expect to see a rise in existential anxiety dur- ing these times, with an increased awareness (or new aware- ness) of mortality.

For some patients, things that used to cause anxiety, such as college coursework and tests, are now more anxiety provoking in new virtual formats.

At the same time, illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are newly emerging in patients.

Patients who have lived with these disorders since before the pandemic may see worse- ning symptoms from added stress and isolation.

During this era of COVID-19, clinicians must continue to use their diag- nostic acumen to consider all possible causes of anxiety.

C is a 23-year-old man who presents to a resident psy- chiatry clinic during the COVID-19 pandemic with a chief complaint of overwhelming anxiety.

Boundary crossings represent devia- tions from the standard frame of treatment that are performed with a therapeutic purpose and are meant to be helpful to the patient.

Boundary violations are de- viations from the standard therapeutic frame that are harmful to the patient and may be meant to benefit the clinician (13).

Visiting a dog shelter with the patient while attempting to preserve the other elements of the treatment frame is meant to help treat the patient and alleviate suffering.

Social dining, intimate physical contact, and disclosing personal problems all lack therapeutic value and risk exploitation of the patient for the therapist’s benefit.

Top Strengthen Your Case with Federal Court Findings There are a number of patient and provider guides for navigating the appeals process that contain complimentary guidance, much of which aligns with the considerations below.

The following proposed appeals strategy builds on current guidance by offering language and approaches for incorporating Wit case findings as a motivating factor for insurers to reconsider care denial decisions.

Several factors contribute to disenrollment, including consolidation and failure of health plans, employer-directed changes in health plans in order to obtain better value, enrollees' search for better drug benefits (1), psychiatric diagnosis (2,3), and overall dissatisfaction with the plan (4).

When a person's health plan is replaced, there may be a sudden disruption to treatment if the enrollee's current behavioral health care provider is not part of the new provider network.

For behavioral health care in particular, disruption to treatment may have dire consequences.

It threatens the therapeutic relationship (5), may result in some anxiety and insecurity on the part of the patient (6), and could even cause serious damage to the therapeutic process.

Persons with mental illness are especially vulnerable.

For example, one study showed that persons with symptoms of depression were less likely to disenroll from a health plan when they were dissatisfied than were enrollees with physical symptoms

Presented here is a model that was used during the transition of 4,075 active commercial and Medicare enrollees from a large medical managed care organization (MCO) to an academic managed behavioral health care organization (MBHO).

The quality of primary care delivery was measured with the Components of Primary Care Instrument, a patient-reported indicator of physician knowledge of the patient, interpersonal communication, coordination of care, continuity of care, and patients' preference to see their regular physician.

Results: No significant differences in any of the five indicators of primary care quality were found between patients with independent provider association/preferred provider organization (IPA/PPO) and fee-for-service insurance.

Patients with IPA/PPO health insurance were four times as likely as patients with fee-for-service insurance to report a forced change in their primary care physician (P < or = .01). Individuals forced to change their physician because of changes in their health care insurance scored significantly lower on all five indicators of primary care quality (P < or = .01). Conclusions: The quality of primary care appears to be less dependent on the payment system than on the maintenance of the patient-physician relationship.

Many individuals do not know they have the right to file an appeal upon receiving an adverse benefit determination.

Health plans and regulators should work together to ensure that all enrollees are aware of their rights through targeted public education campaigns.

Regulators should also reinforce health plans’ parity disclosure requirements and make clear that in both internal and external appeals, a parity violation is grounds for reversal of a coverage denial.

2.

Promote More Due Process and Transparency.

When an adverse benefit determination or denial takes place, more transparency must be provided surrounding how the decision was made and documented.

At a minimum, health plans must disclose the clinical and/or coverage criteria used in the decision and clearly explain the specific steps required to file an appeal.

Regulators should also enforce requirements that denial letters include a detailed explanation of why the patient does not meet the plan’s clinical criteria, a description of the evidence reviewed by the plan, and address evidence submitted by the patient or their provider.

Otherwise, consumers cannot avail themselves of their appeal rights.

Filing An Appeal Based On a Parity Violation The Kennedy Forum • 3.

Allow Attending Providers and other Advocates to File Appeals.

In some instances, ordering or attending providers are not allowed to file an appeal on behalf of their patients.

This is counterintuitive and inefficient as the provider is often in the best position to understand the denial decision and then explain why the service or treatment is still recommended or why the care was already delivered.

Providers also have a “leg-up” as they are familiar with the medical jargon used in the denial letter or throughout the appeals process.

4.

Simplify the Appeals Process.

Many patients and ordering providers complain that too many bureaucratic hurdles and inconsistent requirements exist within the appeals process.

These obstacles have a chilling effect that discourages patients or their representatives from filing an appeal.

Originally, the appeals process made clear that utilization management (UM) appeals handled medical necessity or clinical denials, and grievance procedure appeals handled administrative denials.

Today, model laws from the National Association of Insurance Commissions (NAIC) and many jurisdictions have issued regulations that have eroded this formerly clear bifurcation.

We recommend that one integrated and streamlined appeals process apply no matter the basis of the initial denial.

5.

Standardize the Appeal System Across Market Segments and State Lines.

A national and consistent standard must be implemented to make the appeals process effective.

At present, many different appeal pathways exist.

These pathways vary based on how the health plan is regulated, the type of coverage provided, the type of plan sponsor, the jurisdiction, the type of denial (e.g., based upon a medical necessity or benefit determination), the timing of the denial (e.g., prospective, concurrent and retrospective), the urgency of the care being requested (i.e. standard care versus urgent care), and where the patient is in the appeals process.

Our goal should be to establish one national appeals standard that promotes transparency, fairness and due process to all parties involved.

We can accomplish this unified system through new model legislation, accreditation standards and Requests for Proposal (RFP) requirements.

6.

Upgrade the External Review Appeals Process.

Currently, the patient or their authorized representative must specifically request an external review of their claim.

In most cases, the external review appeal only can be pursued after a patient first successfully completes an appeal through the health plan.

In some instances, the aggrieved party may not even know they have the right to appeal to an external party.

One simple way to address this confusion is to automatically refer the appeal to an independent review organization after the internal appeal is completed.

For example, Medicare beneficiary appeals are automatically referred to the external review level, resulting in more due process.

Filing An Appeal Based On a Parity Violation The Kennedy Forum • In addition, the external review process as currently regulated should be re-examined and potentially upgraded to better protect consumers.

Ideas include: n Reviewer Identification.

In many cases, the patient does not know who made the final ruling during the external review.

Should the identity of the external reviewer be revealed or remain anonymous? Does due process require the person making the judgment to be disclosed like a judge in court? The Kennedy Forum recommends that the identity of the reviewer be routinely disclosed.

Public Disclosure of Decisions.

In some states, regulators post de-identified external appeal decisions on their websites, a practice that allows consumers and providers to understand the types of issues being sent to external appeals, how external decisions are made, and to identify trends (such as frequent overturns of denials of coverage for specific treatments).

Greater disclosure of external appeal decisions would benefit individual consumers and help frame dialogue with health plans regarding practices that should be reformed.

Payment.

In most cases, health plans contract with two or more external review organizations to handle the external reviews of their insured population.

Does the external review organization have an incentive to rule in favor of the health plan if the health plan also is paying for the cost of the external review? Should the patient’s health plan pay for the external review? Or should it be funded by a government agency or through some sort of fund supported by all health plans in a particular jurisdiction? The Kennedy Forum recommends that some sort of payment system be set up through the local jurisdiction rather than through the health plan to avoid any perceived or real conflicts of interest that might bias the external review decision in favor of the health plan.

Exhausting Internal Review.

Should the patient or their advocate always have to exhaust the health plan internal appeals process before filing an external appeal? Should the patient have the right to skip right to external review? The Kennedy Forum recommends that the patient be permitted to skip the internal UM appeals process and go right to external review if that is their decision.

However, once this decision is made, the patient or their advocate loses the right to use the health plan’s internal appeal system for that particular issue under dispute.

Filing An Appeal Based On a Parity Violation The Kennedy Forum • 7.

File More Appeals.

While working to lower the number of denials issued on claims, stakeholders should simultaneously work to ensure that every questionable denial is subjected to the appeals process so that enrollees receive the care they are entitled to.

Each stakeholder group should do the following to promote the filing of appeals: n Consumer/Provider.

Every patient who has experienced a denial or care restriction of mental health or addiction services should file a complaint at and/or with the applicable government agency.

Filing a complaint will help us develop comprehensive data to better understand the different types of parity denials.

n Industry.

When an appeal is filed, health plan personnel must make a good faith effort to respond in a timely and meaningful manner.

Health plans and medical management organizations must ensure they are complying with existing regulations and the patient’s plan documents on how these appeals should be processed (e.g., timeframes, disclosure requirements).

Policymakers/Regulators.

Policymakers and public officials must ensure they enforce existing state and federal regulations on how appeals should be filed and processed.

In addition, the current regulatory and accreditation requirements should be updated to create a more efficient and effective appeals process for all parties.

8.

Leverage Technology to Improve the Efficiency of the Appeals Process.

Much like TurboTax has helped tax filers, it is time to leverage technology to promote a more efficient appeals process.

All too often, the appeals process is still paper-based or otherwise very fragmented.

While is one step in the right direction, more can be done.

9.

Update Regulatory Oversight Mechanisms.

It is time to update regulations to capture recent trends in how best to monitor and promote the appeals process.

This could include updating the model laws, regulations and accreditation standards covering utilization management, grievance procedures, external review and mental health parity compliance, both at the federal and state levels.

It also could include promoting value-based and outcome measures.

Regulations need to keep pace with changes in health care delivery, technology capabilities, and communication platforms.

Filing An Appeal Based On a Parity Violation The Kennedy Forum • 10.

Promote Advocacy and Sponsor Education Programs.

States should sponsor and subsidize experts who can help patients understand, file, and process appeals by creating consumer advocate offices, like the Office of the Health Care Advocate in Connecticut or Health Law Advocates in Massachusetts.

Regulators and health insurers can support this effort through customer service lines, supplemental educational programs, broker materials and other resources that are specific to their agency or plan.

These agencies should also actively connect consumers interested in filing an appeal with non-profits capable of supporting individuals throughout the process.

Final Thoughts The appeals process, especially for parity violations, remains a complex and confusing system for most stakeholders.

It is time to rethink and improve on existing appeal systems with an eye towards making the appeals process more efficient, transparent and meaningful.

The impact of doing so will be meaningful for individuals—and their families—who need and deserve care and are entitled to services.

For more information on this topic, contact Garry Carneal, JD, Senior Policy Advisor, The Kennedy Forum, at info@thekennedyforum.org. See also Organize Your Materials What papers do I need? Keep copies of all information related to your claim and the denial.

This includes information your insurance company provides to you, and information you provide to your insurance company, such as: The Explanation of Benefits (EOB) forms or letters showing what payment(s) or service(s) were denied A copy of the request for an internal appeal that you send to your insurance company Any additional information you send to the insurance company (such as a letter or other information from your doctor) A copy of any letter or form you are required to sign, if you choose to have your doctor or anyone else file an appeal for you.

Keep a diary of phone conversations you have with your insurance company or your doctor that relate to your appeal (include the date, time, name, and title of the person you talked to, as well as details about the conversation) Keep your original documents and submit copies to your insurance company.

You will need to send your insurance company the original request for an internal appeal, and your request to have a third party (such as your doctor) file an internal appeal for you.

Make sure you keep copies of all documents for your records.

What kinds of denials can be appealed? You can file an internal appeal if your health plan won’t pay some or all of the cost for health care services you believe should be covered.

The plan might issue a denial because: The benefit is not offered under your health plan Your medical problem began before you joined the health plan You received health services from a health provider or facility that is not in your health plan’s approved network Your health plan determines the requested service or treatment is “not medically necessary” Your health plan determines the requested service or treatment is an “experimental” or “investigative” treatment You are no longer enrolled or eligible to be enrolled in a health plan Your health plan revokes or cancels your coverage, going back to the date you enrolled, because the insurance company claims you gave false or incomplete information when you applied for coverage

The Kennedy Forum @kennedyforum

American Psychological Association @APA

With more than 121,000 members, the American Psychological Association (APA) advances psychological science to promote health, education and human welfare.

-

American Psychiatric Association Foundation - building a mentally healthy nation for all American Psychiatric Association @APAPsychiatric American Psychiatric Association (APA) is the leading psychiatric organization in the world representing more than 37,400 psychiatrists.

-

LA Health Care Services Division Agency

LSU Health Care Services Division (LSU HCSD) includes Executive Administration and General Support (Central Office) and six (6) hospitals that have entered into cooperative endeavor agreements (CEA) for public-private partnerships and the Lallie Kemp Regional Medical Center.

-

Patient satisfaction is measured using The Myers Group, a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) approved vendor, and is summarized in "overall rating of hospital" and "willingness to recommend hospital." LSU-HCSD has set its performance standards above the state, national and west south regional averages.

LSU-HCSD will follow the CMS rules for reporting; which represents data from a prior quarter being reported due to timing 1: the several campuses as defined below

-

© Copyright, American Psychiatric Association, all rights reserved.

-

Specific administrative strategies for termination and referrals should also be considered, such as, if indicated, provisions for clear communication to the patient that any contact with the previous psychiatrist (who was stalked) may be criminally prosecuted.

-

If a termination letter is sent, it should be by certified mail and include referrals to another professional, and might be better to come from the administrative director or clinic rather than the psychiatrist who was stalked (Pinals et al., 2007).

-

However, there should also be a careful determination of what if any final contact should be generated from the psychiatrist with clear instruction that leaves no room for ambiguity.

-

If the patient is being referred to an out-of-system provider, then ethical and legal transfer of information is important.

-

The psychiatrist (who was stalked) should develop a strategy to manage any future contacts - for example, one way to address the issues is that once the patient care has been terminated, it might be prudent for the psychiatrist who was stalked to not respond directly to the ex-patient’s future contacts.

-

Instead the hospital risk management division should send a clear and polite letter stating that it is hospital policy for the psychiatrist not to respond to the ex-patient, but to address the ex-patient’s needs through the hospital system (e.g., a request for a release of records).

-

The psychiatrist who will be taking on the treatment of the patient should also carefully consider unique challenges in these situations, such as “stalking by proxy,” which in this case reflects when the patient passes notes or communication to their previous psychiatrist through their new psychiatrist (Carr et al., 2013).

-

© Copyright, American Psychiatric Association, all rights reserved.

Resources for the Patient A final issue of paramount importance is how to continue providing care in some way for the patient or how to safely refer the patient to the next psychiatrist who may need information as to the reason for the transfer.

There is a fiduciary duty on the part of the physician that needs to be balanced against concerns for their safety.

Depending on the location where the stalking is occurring, several options for patient care include transferring to a different provider in the same location (but possibly in another building) or transferring the patient to another provider altogether.

APA also supports the inclusion of the Behavioral Health Integration codes (99492-99494, G2214, and 99484) in the definition of primary care services for the Shared Savings Program.

Modifications Related to Medicare Coverage for Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) Treatment Services Furnished by Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs) (section III.O.) We appreciate the two proposed changes included in this section to improve access to care for patients with opioid use disorder by allowing payment for a recently FDA-approved higher dose of naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray product to treat opioid overdose.

We also support allowing the therapy and counseling portions of the weekly bundles, and any additional counseling or therapy provided by opioid treatment programs, to be furnished using audio-only telephone calls rather than via two-way interactive audio/ video communication technology for the duration of the PHE for COVID–19.

This is important given many patients do not have smart phones that allow for two- way communication.

APA appreciates CMS’ intent to align the Provide Patient Electronic Access to Their Health Information measure with the look-back period finalized in the Patient Access and Interoperability final rule.

While the January 1, 2016 date seems reasonable for ECs, the APA recommends that CMS delay enforcement discretion from July 1, 2021, to the end of CY 2021, to account for the ongoing COVID-19 PHE.

Moreover, APA seeks clarification that, during this lookback period, and other proposed future accessibility requirements around changes to the Provide Patient Access PI measure, that ECs can exercise the pertinent Exceptions under the Information Blocking and Interoperability Final Rule.

Specifically, that the Infeasibility, Content and Manner, and Health IT Performance Exceptions may be employed, when applicable, by the EC, when maintaining patient data in near-perpetuity may not be possible for MIPS- eligible clinicians.

Additionally, APA seeks clarification on whether this change to the Provide Patient Access measure will only apply to the reporting years for which the clinician was eligible and did not meet any of the MIPS program exceptions, such as the low-volume threshold.

Clarifying the above points will help to reduce burden among solo and small group psychiatrist ECs who may not participate in MIPS in consecutive years.

Reweighting Promoting Interoperability Performance Category for MIPS Eligible Clinicians in Small Practices

APA appreciates CMS’ continued efforts to reduce administrative and financial reporting burden for small practices endeavoring to participate in MIPS.

(ii) We are proposing to add a new SAFER Guides measure to the Protect Patient Health Information objective...we are proposing that a MIPS eligible clinician must attest to having conducted an annual self assessment using the High Priority Practice Guide, at any point during the calendar year...with one “yes/no” attestation statement accounting for the complete self-assessment using the guide.Generally, the APA supports the use of the Safety Assurance Factors for EHR Resilience (SAFER) Guides, particularly the High Priority Practices Guide, as a part of the Promoting Interoperability performance category.

Requiring ECs to attest to completing these guides has the potential to help many clinicians enhance and optimize health IT, ensuring that they are “responsible operators of technology tools,” as stated in this proposed rule.

This attestation is reminiscent of the existing Security Risk Assessment measure in its utility to safeguard patient information, and in that it will not be scored for PI.

While we appreciate CMS’ acknowledgement ECs (especially those in solo or small group practice) vary in terms of resources with respect being able to complete the SAFER attestation annually, APA recommends that, for the 2022 RY, CMS conduct an audit of those entities that attest “no,” in order to ascertain why they did not complete a SAFER attestation, to see if additional resources might support them in doing so for future reporting years.

(e) We are also more broadly soliciting public comment to help us better understand the resource costs for services involving the use of innovative technologies, including but not limited to software algorithms and AI.In addition to this broader prompt, CMS poses a list of questions for consideration regarding the use of innovative technologies within physician practices.

For example, the Rule considers how technologies, 15 such as AI, have affected physician work time and intensity of furnishing services (e.g., possibly reducing the amount of time that a practitioner spends time reviewing and interpreting results of diagnostic testing), or how technologies are changing cost structures, affecting access to services for Medicare beneficiaries, and more.

While APA and psychiatry continues apace in adopting new technologies into clinical workflows—such as adjunctive therapeutic mobile applications, and wearables—it is qualitatively different from how other specialties are using it.

For example, in the Rule, CMS uses examples such as a simulation software analysis of functional data to assess the severity of coronary artery disease and how trabecular bone score software can supplement physician work to predict and detect fracture risk.

These examples might be considered as straightforward use cases of emerging technology where an attempt to codify and quantify their value to Medicare practitioners and beneficiaries seems reasonable.

For psychiatry some analogous use cases, such as various emerging technologies utilizing focused on discrete physiological symptoms (e.g., neuropsychiatry, movement disorders, clinical decision support, work on neurolinguistics in detecting changes in language use patterns in predicting psychopathy or dementia); however, presently, there are too few datapoints and replicated research into how AI or other technologies are or can affect psychiatric work flows, physician time, and other considerations as contemplated in this Rule.

The use of AI in healthcare is still nascent.

With respect to psychiatry, most AI-driven tools are embedded within health IT products more appropriately described as “augmented intelligence” rather than “artificial intelligence.” The scope of this technology tends to encompass features of electronic health records (EHRs), such as electronic clinical decision support (eCDS), and in Health, such as apps that rely on patients’ behavioral history to send warnings to the patient about environmental factors that could potentially be triggering for mental health conditions, such as substance use disorders.

While APA is optimistic that the future of AI may improve patient care and lead to better outcomes, we are concerned that there are presently very few standards to which industry is being held in the development of AI in healthcare.

For instance, standards around privacy, security, and confidentiality within health IT is currently in flux.

There are also limited regulatory standards on the development and implementation of AI tools, which further complicates how such tools may be accounted for in terms of quality care and outcomes when integrated into Medicare payment considerations.

Do you have a policy on circumstances that may lead to terminating the relationship with a patient? Does the policy include the state requirements to properly terminate the relationship? The APA is also concerned around background development of AI systems that may not include specific populations within standardization samples in AI beta testing/research studies.

Presently, some algorithms may be based solely on a certain population for various medical conditions (e.g., men or women; various ethnicities; various socioeconomic groups) resulting in algorithms that may not compute the best treatment options or interventions for patients with unique vulnerabilities (e.g., developmental disorders, suicidal ideation, substance use disorders).

Before the technology can be incorporated into Medicare payment models, there needs to be a comprehensive examination (by CMS, the FDA, other entities), of which data are being used to develop any algorithms that influence physician decision-making and patient care.

There needs to be an assurance that AI helps patients regardless of one’s race/ethnicity or other social determinants of health and isn’t introducing or magnifying disparities.

Reporting Requirements

Eligible entities are responsible for meeting specific querying and/or reporting requirements and must register with the NPDB in order to query or report to the NPDB. Entities may qualify as more than one type of eligible entity. In such cases, the entity must comply with all associated querying and reporting responsibilities.

Table E-1: Summary of Reporting Requirements, Part 1

Law Who Reports? What is Reported? Who is Reported? Title IV Medical malpractice payers, including hospitals and other health care entities that are self-insured Medical malpractice payments resulting from a written claim or judgment Practitioners State medical and dental boards Certain adverse licensure actions related to professional competence or conduct

(Medical and dental boards that meet their reporting requirements for Section 1921, described in Part 2 of this table, will also meet their requirements to report under Title IV) Physicians and dentists Hospitals

Other health care entities with formal peer review Certain adverse clinical privileges actions related to professional competence or conduct Physicians and dentists

Other practitioners (optional) Professional societies with formal peer review Certain adverse professional society membership actions related to professional competence or conduct Physicians and dentists

Other practitioners (optional) DEA DEA controlled-substance registration actions* Practitioners OIG Exclusions from participation in Medicare, Medicaid, and other federal health care programs* Practitioners* This information is reported to the NPDB under Title IV based on a memorandum of understanding.

Table E-1: Summary of Reporting Requirements, Part 2

Law Who Reports? What is Reported? Who is Reported? Section 1921 Peer review organizations Negative actions or findings by peer review organizations Practitioners Private accreditation organizations Negative actions or findings by private accreditation organizations Entities, providers, and suppliers State licensing and certification authorities State licensure and certification actions Practitioners, entities, providers, and suppliers State law enforcement agencies*

The reporting requirements summarized in Table E-1 are described in greater detail in this chapter. As shown in the table, each of the three major statutes governing NPDB operations has its own reporting requirements. In some instances, actions must be reported based on memorandums of understanding. In certain cases, requirements may exist under more than one statute, or under both a statute and a memorandum of understanding. For example, as discussed in Chapter B: Eligible Entities, the Drug Enforcement Administration's (DEA's) controlled-substance registration actions are reported to the NPDB under Title IV based on a memorandum of understanding; the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General's (OIG's) exclusions from Medicare, Medicaid, and other federal health care programs are reported to the NPDB under Title IV based on an interagency agreement. Both DEA and OIG actions also must be reported to the NPDB under Section 1128E.

Terminology Differences

An action must be reported to the NPDB based on whether it satisfies NPDB reporting requirements and not based on the name affixed to the action by a reporting entity. For example, whether an administrative fine is reportable to the NPDB depends upon whether the fine meets NPDB reporting requirements, not on the name affixed to the fine. A suspension or restriction of clinical privileges is reportable if it meets reporting criteria, whether the suspension or restriction is called summary, immediate, emergency, precautionary, or any other term.

Time Frame for Reporting

Eligible entities must report medical malpractice payments and other required actions to the NPDB within 30 calendar days of the date the action was taken or the payment was made.

The time frame for reporting each type of action described in Table E-1 is summarized in Table E-2.

Types of Actions that Must Be Reported When Information Must be Reported Medical malpractice payments

Certain adverse licensure actions related to professional competence or conduct (reported under Title IV)

Certain adverse clinical privileges actions related to professional competence or conduct

Certain adverse professional society membership actions related to professional competence or conduct

DEA controlled-substance registration actions on practitioners (reported under Title IV)

Exclusions from participation in Medicare, Medicaid, and other federal health care programs (reported under Title IV) Within 30 days of the date the action was taken or the payment was issued, beginning with actions occurring on or after September 1, 1990 Negative actions or findings taken by peer review organizations

Negative actions or findings taken by private accreditation organizations Within 30 days of the date the action was taken, beginning with actions occurring on or after January 1, 1992 State licensure and certification actions

Federal licensure and certification actions

Health care-related criminal convictions in federal or state court

Health care-related civil judgments in federal or state court

Exclusions from participation in a federal or state health care program.

Other adjudicated actions or decisions Within 30 days of the date the action was taken, beginning with actions occurring on or after August 21, 1996

The NPDB cannot accept reports with a date of payment or a date of action prior to September 1, 1990, with the exception of Medicare and Medicaid exclusions submitted by the OIG.

If an eligible entity discovers documentation of medical malpractice payments, adverse actions, or judgments or convictions that the eligible entity had not reported to the NPDB, the entity must promptly submit the related report(s). All required reports must be filed with the NPDB regardless of whether they are late.

Entities are not excused from reporting simply because they missed a reporting deadline. The Secretary of HHS will conduct an investigation if there is reason to believe an entity substantially failed to report required medical malpractice payments or adverse actions. Entities have the opportunity to correct the noncompliance (see "Sanctions for Failing to Report" to the NPDB in the sections discussing the reporting requirement for each type of action).

Deceased Practitioners

One of the principal objectives of the NPDB is to restrict the ability of incompetent physicians, dentists, and other health care practitioners to move from state to state without the disclosure or discovery of their previous damaging or incompetent performance. Reports concerning deceased practitioners must be submitted to the NPDB because a fraudulent practitioner could assume the identity of a deceased practitioner. When submitting a report on a deceased practitioner, indicate that the practitioner is deceased in the appropriate data field.

Report Retention

Information reported to the NPDB is maintained permanently in the NPDB, unless it is corrected or voided from the NPDB by the reporting entity or by the NPDB as a result of the Dispute Resolution process.

Civil Liability Protection

The immunity provisions in Title IV, Section 1921, and Section 1128E protect individuals, entities, and their authorized agents from being held liable in civil actions for reports made to the NPDB unless they have actual knowledge of falsity of the information contained in the report. These provisions provide the same immunity to HHS in maintaining the NPDB.

Louisiana Department of Health announces new Medicaid Executive Director

September 09, 2021Patrick Gillies has joined the Louisiana Department of Health as the new Medicaid Executive Director.

Gillies has more than 20 years of experience in healthcare administration on both the state and federal levels. He most recently worked as an independent consultant assisting organizations with operations including healthcare systems operations, Medicare and Medicaid.

In previous roles, Gillies worked with organizations to support their participation in the 340B Drug Discount Program and provided leadership and accountability for the Medicaid line of business for three Regional Care Collaborative Organizations (RCCOs) set up through the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing's Accountable Care Collaborative (ACC).

He has also served as a regional administrator for Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) and as the Director of Community Health for the Texas Department of State Health Services.

Gillies holds a Master of Public Administration in Health Policy & Administration from Texas Tech University.

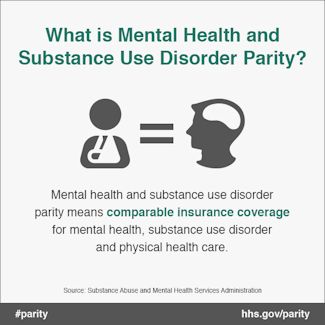

The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA)

The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA) is a federal law that prevents health care service plans from imposing more restrictive benefit limitations on mental health and substance use disorder (MH/SUD) benefits than on medical/surgical coverage.

Health plans must ensure that financial requirements (such as co-pays and deductibles) and treatment limitations that apply to MH/SUD benefits are no more restrictive than the predominant requirements or limitations applied to medical and surgical benefits.

Louisiana Medicaid will complete a compliance review of all services by October 2, 2017. This initiative will ensure Louisiana Medicaid recipients receiving Medicaid and CHIP services receive equal access to physical and behavioral health care.

Legislative History

- 1996: Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 (MHPA) Required certain commercial group health coverage have parity in aggregate lifetime and dollar limits

- 2008: Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) Added substance use disorder services and required parity in treatment/financial limitations

- 2013: Final mental health parity rules for commercial plans

- 2016: Final mental health parity rules for Medicaid and CHIP managed care organizations (MCOs)

Classifications

- Louisiana will place each Medicaid service in the following four classifications required in parity analysis:

- Inpatient

- Outpatient

- Emergency Care

- Prescription Drugs

Treatment Limitations to be Analyzed

- Quantitative Treatment Limitations: Limits on benefits based on the frequency of treatment; examples include:

- Number of visits

- Days of coverage

- Days in a waiting period, or

- Other similar limits on the scope or duration of treatment

- Non-Quantitative Treatment Limitations: No “hard limits” but limit the ability of a person to receive a certain service or level of services; examples include:

- Prior Authorization Processes

- Concurrent Review

- “Fail First” Policies

Notice.

Notice. If CMS decides to terminate a contract it gives notice of the termination as follows:

(1) Termination of contract by CMS.

(i) CMS notifies the MA organization in writing at least 45 calendar days before the intended date of the termination.

(ii) The MA organization notifies its Medicare enrollees of the termination by mail at least 30 calendar days before the effective date of the termination.

(iii) The MA organization notifies the general public of the termination at least 30 calendar days before the effective date of the termination by releasing a press statement to news media serving the affected community or county and posting the press statement prominently on the organization's Web site.

(iv) In the event that CMS issues a termination notice to an MA organization on or before August 1 with an effective date of the following December 31, the MA organization must issue notification to its Medicare enrollees at least 90 days prior to the effective date of the termination.(2) Immediate termination of contract by CMS.

(i) The procedures specified in paragraph (b)(1) of this section do not apply if -

(A) CMS determines that a delay in termination, resulting from compliance with the procedures provided in this part prior to termination, would pose an imminent and serious risk to the health of the individuals enrolled with the MA organization; or

(B) The MA organization experiences financial difficulties so severe that its ability to make necessary health services available is impaired to the point of posing an imminent and serious risk to the health of its enrollees, or otherwise fails to make services available to the extent that such a risk to health exists; or

(C) The contract is being terminated based on the grounds specified in paragraph (a)(4)(i) of this section.

(ii) CMS notifies the MA organization in writing that its contract will be terminated on a date specified by CMS. If a termination is effective in the middle of a month, CMS has the right to recover the prorated share of the capitation payments made to the MA organization covering the period of the month following the contract termination.

(iii) CMS notifies the MA organization's Medicare enrollees in writing of CMS's decision to terminate the MA organization's contract. This notice occurs no later than 30 days after CMS notifies the plan of its decision to terminate the MA contract. CMS simultaneously informs the Medicare enrollees of alternative options for obtaining Medicare services, including alternative MA organizations in a similar geographic area and original Medicare.

(iv) CMS notifies the general public of the termination no later than 30 days after notifying the plan of CMS's decision to terminate the MA contract. This notice is published in one or more newspapers of general circulation in each community or county located in the MA organization's service area.

42 CFR § 422.510

Scoping language

Termination by CMS. CMS may at any time terminate a contract if CMS determines that the MA organization meets any of the following:

(1) Has failed substantially to carry out the contract.

(2) Is carrying out the contract in a manner that is inconsistent with the efficient and effective administration of this part.

(3) No longer substantially meets the applicable conditions of this part.(4) CMS may make a determination under paragraph (a)(1), (2), or (3) of this section if the MA organization has had one or more of the following occur:

(i) Based on creditable evidence, has committed or participated in false, fraudulent or abusive activities affecting the Medicare, Medicaid or other State or Federal health care programs, including submission of false or fraudulent data.-

(ii) Substantially failed to comply with the requirements in subpart M of this part relating to grievances and appeals.

-

- (iii) Failed to provide CMS with valid data as required under § 422.310.

-

- (iv)

Failed to implement an acceptable quality assessment and performance

improvement program as required under subpart D of this part.

-

- (v) Substantially failed to comply with the prompt payment requirements in § 422.520.

-

- (vi) Substantially failed to comply with the service access requirements in § 422.112 or § 422.114.

-

- (vii) Failed to comply with the requirements of § 422.208 regarding physician incentive plans.

-

- (viii) Substantially fails to comply with the requirements in subpart V of this part.

-

(ix) Failed to comply with the regulatory requirements contained in this part or part 423 of this chapter or both.

-

- (x)

Failed to meet CMS performance requirements in carrying out the

regulatory requirements contained in this part or part 423 of this

chapter or both.

-

- (xi)

Achieves a Part C summary plan rating of less than 3 stars for 3

consecutive contract years. Plan ratings issued by CMS before September

1, 2012 are not included in the calculation of the 3-year period.

-

- (xii)

Has failed to report MLR data in a timely and accurate manner in

accordance with § 422.2460 or that any MLR data required by this subpart

is found to be materially incorrect or fraudulent.

-

- (xiii) Fails to meet the preclusion list requirements in accordance with § 422.222 and 422.224.

-

- (xiv)

The MA organization has committed any of the acts in § 422.752(a) that

support the imposition of intermediate sanctions or civil money

penalties under subpart O of this part.

-

(a) courtesy, respect, dignity, and timely, responsive attention to his or her needs.

(b) To receive information from their physicians and to have opportunity to discuss the benefits, risks, and costs of appropriate treatment alternatives, including the risks, benefits and costs of forgoing treatment. Patients should be able to expect that their physicians will provide guidance about what they consider the optimal course of action for the patient based on the physician’s objective professional judgment.

(c) To ask questions about their health status or recommended treatment when they do not fully understand what has been described and to have their questions answered.

(d) To make decisions about the care the physician recommends and to have those decisions respected.

A patient who has decision-making capacity may accept or refuse any recommended medical intervention.

(e) To have the physician and other staff respect the patient’s privacy and confidentiality.

(f) To obtain copies or summaries of their medical records.

(g) To obtain a second opinion.

(h) To be advised of any conflicts of interest their physician may have in respect to their care.

(i) To continuity of care. Patients should be able to expect that their physician will cooperate in coordinating medically indicated care with other health care professionals, and that the physician will not discontinue treating them when further treatment is medically indicated without giving them sufficient notice and reasonable assistance in making alternative arrangements for care.

- President and the academic officers of the University

- 2: fulfill the duties of the faculty.

- The Board, the President, and the Chancellors will rely on those elected 3: which, in the judgment of the Chancellor, or of the President, is administrative or which seriously affects 4: or of the University itself, may be suspended by the President and such action shall be reported to the Board 5: or, for LSU or in inter-campus situations, by the President.

- Meetings.

- Each faculty, or its representative 6: for that purpose may be called at the request of the President as chair or of the Chancellor of the campus or, 7: shall be given.

- It shall be the prerogative of the President to preside; otherwise, the Chancellor of the 8: officer concerned, shall be reported to the President.

- The President may then refer any such action on 9: concerned, shall be reported to the President.

- The President may then refer any such action on academic 10: the several campuses as defined below

- The President and the academic officers of the University 11: fulfill the duties of the faculty.

- The Board, the President, and the Chancellors will rely on those elected 12: which, in the judgment of the Chancellor, or of the President, is administrative or which seriously affects 13: or of the University itself, may be suspended by the President and such action shall be reported to the Board 14: or, for LSU or in inter-campus situations, by the President.

- a Minutes of all actions taken by the faculties 15: officer concerned, shall be reported to the President.

- The President may then refer any such action on 16: concerned, shall be reported to the President.

- The President may then refer any such action on academic 17: purpose may be called at the call request of the President as chair or of the Chancellor of the campus or, 18: shall be given.

- It shall be the prerogative of the President to preside; otherwise, the Chancellor of the 19: officer concerned, shall be reported to the President.

- The President may then refer any such action on 20: concerned, shall be reported to the President.

- The President may then refer any such action on academic

- 21: that should be brought to the attention of the President and Board 5.

- An explanation of any significant 22: to the reporting format will be approved by the President with notification to the Board.

- ARTICLE I ACADEMIC AND ADMINISTRATIVE ORGANIZATION

- Duties.

- Under the Constitution of the State of Louisiana, the Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College has the authority to organize and manage the university.

- The Board authorizes the general body of the faculty, or its representative body, to establish curricula, fix standards of instruction, determine requirements for degrees, make recommendations for the granting of degrees through its respective colleges or schools not within a college and generally determine educational policy, subject to the authority of the Board.

- Except as otherwise provided, each faculty shall establish its own educational policies.

- The Board authorizes the faculty to establish admissions criteria for graduate and professional programs, however, standards for undergraduate admission to the University shall be approved by the Board.

The terms faculty and Faculty Council are used interchangeably in this Section (2).

Faculty Representative Body.

Except as otherwise provided, the faculty of each campus shall establish its own governance policies.

The faculty may establish one representative body, such as a Senate or committee, to represent the will of the faculty and exercise legislative power to conduct its own meetings and fulfill the duties of the faculty.

The Board, the President, and the Chancellors will rely on those elected representative bodies as the voice of the general faculty.

Actions.

Any action of a faculty or Faculty Council which faculty representative body which, in the judgment of the Chancellor, or of the President, is administrative or which seriously affects the interests of another faculty of the University or of the University itself, may be suspended by the President and such action shall be reported to the Board at its next meeting.

All questions of jurisdiction among colleges, schools not within colleges, or divisions shall be determined by the Chancellor, or, for LSU or in inter-campus situations, by the President.

Minutes of all actions taken by the faculties or Faculty Councils, together with appropriate recommendations of the major administrative officer concerned, shall be reported to the President.

The President may then refer any such action on academic matters of general University concern to the appropriate council, or a committee thereof, for consideration.

4.

Meetings.

Each faculty, or its representative body, or Faculty Council shall meet at least once each academic year.

For the purpose of replacing or reconstituting the representative body, a meeting of the general faculty for that purpose may be called at the call request of the President as chair or of the Chancellor of the campus or, for LSU, the President’s designee, as vice-chair, or upon the written request of 50 members or 20 percent of the membership, whichever is the smaller number fewer.

The written request must be received within a 14-day period from the time of the original solicitation.

At least five days notice of meeting shall be given.

It shall be the prerogative of the President to preside; otherwise, the Chancellor of the campus or, for LSU, the President’s designee, will preside.

- Key AcronymsThe following abbreviations are used in this Guide, and are defined in the glossary or within the text:ACA—The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (see also PPACA) AHP—Association Health Plan CMS—U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services COC—Certificate of Coverage DOL—U.S. Department of Labor EAP—Employee Assistance Program EHBs—Essential Health Benefits EOB—Explanation of Benefits EOC—Evidence of Coverage EPO—Exclusive Provider Organization ERISA—Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 FDA—U.S. Food and Drug Administration FEHB Program—Federal Employees Health Benefits Program FFS—Fee-for-Service FR—Financial Requirement HDHP—High Deductible Health Plans HHS—U.S. Department of Health and Human Services HIPAA—Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act HMO—Health Maintenance Organization HSA—Health Savings Account IOP—Intensive Outpatient Program IRO—Independent Review Organization MBHO—Managed Behavioral Health Organization MEWA—Multiple Employer Welfare Arrangement Plans MH/SUD—Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders MHPAEA—The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, also known as the Federal Parity Law NQTL—Non-Quantitative Treatment Limitation PCP—Primary Care Provider PHP—Partial Hospitalization Program PPACA—The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (see also ACA) POS—Point of Service PPO—Preferred Provider Organization QTL—Quantitative Treatment Limitation SBC—Summary Benefits and Coverage SPD—Summary Plan Description TPA —Third Party Administrator UCR—Usual, Customary and Reasonable UM—Utilization Management Call to Action:Although many success stories exist where a patient or ordering provider’s appeal was handled in a timely and efficient manner by a health plan, those cases are the exception and not the norm.

Additional Resources

- Louisiana Parity Report

- LDH Mental Health Parity FAQ

- LDH Parity 101

- Louisiana Department of Insurance Parity Website

- MHPAEA Factsheet

- Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008

- Department of Labor's Mental Health Parity FAQ

Additional Resources

-

FY22-23 Block Grant Application- Draft

-

FY21 Mini Block Grant Application-Draft

-

2020-2021 Louisiana Combined Behavioral Health Block Grant Application

-

2018-2019 Louisiana Combined Behavioral Health Block Grant Application

-

2016-17 Louisiana CMHS and SAPT Combined Block Grant Application

-

Click here to submit comments related to the 2016-17 Block Grant Application/Plan

-

2014 Louisiana CMHS and SAPT Combined Block Grant Application

Mailing Address

P.O. Box 4049

Baton Rouge, LA 70821-4049Contact Information

Government Sites

Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS)

CMS – Payment Error Rate Measurement (PERM)

DHH Office of Aging and Adult Services

DHH Division of Fiscal Management Page

Louisiana Board of Pharmacy

Louisiana Medicaid News

Louisiana Medicaid Program Home Page (BHSF)

Louisiana State Board of Dentistry

Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners

Louisiana State Board of Optometry Examiners

Melanie Roberts, MS

225.892.2329

melanie.roberts@la.govMailing Address

P.O. Box 4049

Baton Rouge, LA 70821-4049Contact Information

Staff

Melanie Roberts

LBHAC Liaison

225.892.2329

P.O Box 40517

Baton Rouge, LA 70835Anthony Germade

LBHAC Chair

225.291.6262

NAMI Louisiana, National Alliance on Mental Illness

307 France Street, Ste. A

Baton Rouge, LA 70802Katelyn Burns

LBHAC Support Staff

225.291.6262