Sivad Tribute to Fantastic Features

Every now and then Fly on the Wall likes to publish something "From the Morgue," which, in newspaper jargon, means an article we published some time in the past that's been filed away.

But in this case the expression's especially fitting. It's late October — time to remember Memphis' original horror host Sivad.

The horror first took control of Memphis television sets at 6 p.m. Saturday, September 29, 1962. It began with a grainy clip of black-and-white film showing an ornate horse-drawn hearse moving silently through a misty stretch of Overton Park.

Weird music screeched and swelled, helping to set the scene. A fanged man in a top hat and cape dismounted. His skin was creased, corpse-like. He looked over his shoulder once, then dragged a crude, wooden coffin from the back of the hearse. His white-gloved hand opened the lid, releasing a plume of thick fog and revealing the bloody logo of Fantastic Features.

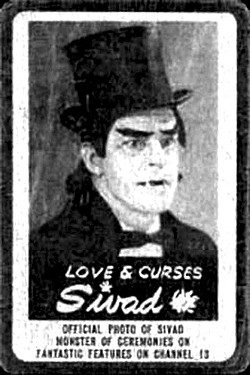

"Ah. Goooood eeeevening. I am Sivad, your monster of ceremonies," the caped figure drawled, in an accent that existed nowhere else on planet Earth. Think: redneck Romanian.

"Please try and pay attention," he continued, "as we present for your enjoyment and edification, a lively one from our monumental morgue of monstrous motion pictures."

In that moment, a Mid-South television legend was born. For the next decade, Sivad, the ghoulish character created by Watson Davis, made bad puns, told painfully bad jokes, and introduced Memphians to films like Gorgo...

The Brain That Wouldn't Die...

and Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent.

via GIPHY

Watson Davis' wisecracking monster wasn't unique. He was one of many comically inclined horror hosts who became popular regional TV personalities from the '50s through the '70s. According to John Hudgens, who directed American Scary, a documentary about the horror-host phenomenon, it all began with "Vampira," a pale-skinned gorgon immortalized by Ed Wood in his infamously incompetent film Plan 9 From Outer Space.

Although a Chicago-area host calling himself "The Swami" may have been the first costumed character regularly introducing scary movies on television, the big bang of horror hosting happened in 1954, when the wasp-wasted actress Maila Nurmi introduced her campy, Morticia Adams-inspired character on The Vampira Show, which aired in Los Angeles.

In 1957, Screen Gems released a package of 52 classic horror films from Universal studios. The "Shock Theater" package, as it was called, created an opportunity for every market to have its own horror host. "Part of that package encouraged stations to use some kind of ghoulish host," Hudgens explains. "Local television was pretty much live or had some kind of host on everything back then."

Overnight, horror hosts such as New York's "Zacherly" and Cleveland's "Ghoulardi" developed huge cult followings.

"TV was different in those days," Hudgens says. "There weren't a lot of channels to choose from, and the hosts could reach a lot more people quickly. Ghoulardi was so popular that the Cleveland police actually maintained that the crime rate went down when his show was on the air, and they asked him to do more shows."

Tennessee's first horror host was "Dr. Lucifer," a dapper, cheeseparing man of mystery who hit the Nashville airwaves in 1957.

Since Fantastic Features didn't air until the fall of 1962, Sivad was something of a latecomer to the creep-show party. But unlike most other horror hosts, Davis didn't have a background in broadcasting. He'd been a movie promoter, working for Memphis-based Malco theaters. His Sivad character existed before he appeared on television. At live events, he combined elements of the classic spook show with an over-the-top style of event-oriented marketing called ballyhoo. So Davis' vampire, while still nameless, was already well known to local audiences before Fantastic Features premiered.

"You've got to understand, things were very different back then," Elton Holland told the Memphis Flyer in a 2010 interview.

"Downtown Memphis was a hub for shopping, and going out to the movies was an event. And back then, Malco was in competition with the other downtown theaters, so when you came to see a movie, we made it special.”

To make things special Holland, Davis, and Malco vice president Dick Lightman became masters of promotion and special events. Davis and Holland were neighbors who lived in Arkansas and car-pooled into Memphis every day. During those drives, Davis would float ideas for how to promote the films coming to town.

The studios only provided movie theaters with limited marketing materials. Theater businesses had in-house art departments that created everything else. What the art department couldn't make, Davis built himself in the theater's basement. When 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea came to town, he built a giant squid so large it had to be cut in half to get it up the stairs. He constructed a huge King Kong puppet that towered over the lower seats. For the film Dinosaurus, he built a Tyrannosaurus rex that was 20 feet tall and 45 feet long. It sat in the lobby, roaring and moving its tail.

"All movies were sold through exploitation," Holland explained. "And horror movies were the best ones to exploit. ... I remember when Watson first told me he wanted to be a monster. He was thinking vaudeville. He wanted to put on a show."

Davis' plan to create a scary show wasn't original. The "spook show" was a sideshow con dating back to when 19th-century snake-oil vendors traveled the country hawking their wares. Slick-talking performers would hop from town to town promising entertainment-deprived audiences the chance to see a giant, man-eating monster, so terrible it had to be experienced to be believed. Once the tickets were sold, it was loudly announced that the monster had broken free and was on a bloody rampage. The idea was to cause panic and create a confusing cover for the performers to make off with the loot.

In the early 20th century, the spook show evolved, and traveling magicians exploited the public's growing fascination with spiritualism by conjuring ghosts and spirits. By mid-century, they developed into semi-comical "monster shows" that were almost always held in theaters. Today's "hell houses" and haunted mansions are recent permutations of the spook show.

When England's Hammer Films started producing horror movies that were, as Holland says, "a cut above," he, Davis, and Lightman took the old spook-show concept and adapted it sell movie tickets. They went to Memphis State's drama department and to the Little Theatre [now Theatre Memphis] looking for actors so they could put a monster on a flatbed truck in front of the Malco.

Davis dressed as Dracula, Holland was the Hunchback of Notre Dame, and another Malco exec played Frankenstein. The company also included a wolfman and a mad doctor.

Davis sometimes joined Lightman on inspection tours of other Malco properties. On one of those tours, the men saw an antique horse-drawn hearse for sale on the side of the road. They bought the hearse that appears in the Fantastic Features title sequence for $500. It also appeared in various monster skits and was regularly parked in front of Malco theaters to promote horror movies.

"One time we had this actor made up like a wild man," Holland said, recalling a skit that was just a little too effective. "While Watson did his spiel about the horror that was going to happen, the chained wild man broke loose and pretended like he was attacking this girl. He was going to jerk her blouse and dress off, and she had on a swimsuit underneath." One 6'-3", 300-pound, ex-military Malco employee wasn't in on the joke and thought the actor had actually gone wild. He took the chain away, wrapped it around the wild man's neck, and choked him until the two were pulled apart. The proliferation of television eventually killed ballyhoo promotions and all the wild antics used to promote movies. At about that time, the studios started "going wide" with film distribution, opening the same film in many theaters at one time instead of just one theater in every region. This practice made location-specific promotions obsolete. By then, the Shock Theater package had made regional stars out of horror hosts all across the country. WHBQ approached Davis and offered him the job of "monster of ceremonies" on its Fantastic Features show. The show found an audience instantly and became so popular that a second weekly show was eventually added. Memphis viewers apparently couldn't get enough of films like Teenage Caveman...

And Mutiny in Outer Space...

Joe Bob Briggs, cable TV's schlock theater aficionado who hosted TNT's Monster Vision fro m 1996 to 2000, says that "corny" humor was the key to any horror host's success or failure. "Comedy and horror have only rarely been successfully mixed in film — although we have great examples like Return of the Living Dead, Briggs says. "But comedy surrounding horror on television was a winning formula from day one. In fact, it's essential. If you try to do straight hosting on horror films, the audiences will hate you."

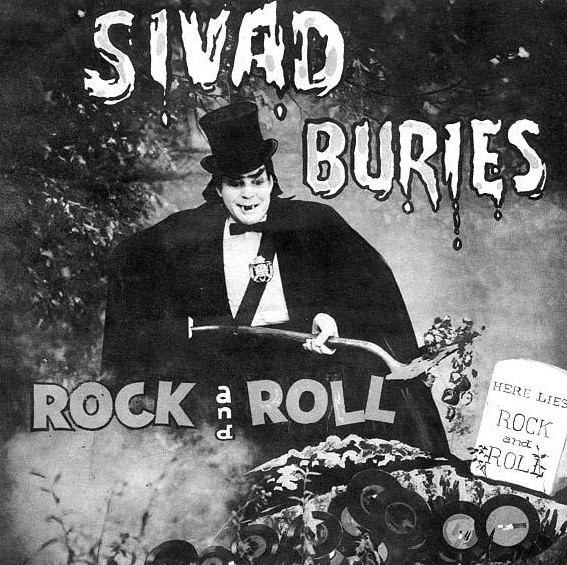

In 1958, Dick Clark invited New York horror host Zacherly to appear on American Bandstand. "This wasn't the year for the comedians, this was the year for the spooks and the goblins and the ghosts," Clark said, introducing "Dinner With Drac," the first hit novelty song about monsters. Four years later, Bobby "Boris" Puckett took "Monster Mash" to the top of the charts. In the summer of 1963, Memphis' favorite horror host hopped on the pop-song monster bandwagon by recording the "Sivad Buries Rock and Roll/Dicky Drackeller" single.

Novelty songs such as "What Made Wyatt Earp" became a staple on Fantastic Features, and Sivad began to book shows with the King Lears, a popular Memphis garage band that influenced contemporary musicians like Greg Cartwright, who played in the Oblivians and the Compulsive Gamblers before forming the Reigning Sound. Although "Sivad Buries Rock and Roll" never charted, Goldsmith's department store hosted a promotional record-signing event, and 2,000 fans showed up to buy a copy.

In 1972, Fantastic Features was canceled. And though Davis was frequently asked to bring the character back, he never did. Horror movies were changing, becoming bloodier and more sexually explicit in a way that made them a poor fit for Sivad's family-friendly fright-fest. In 1978, Commercial Appeal reporter Joseph Shapiro unsuccessfully tried to interview Davis. He received a letter containing what he called a cryptic message:

"Sivad is gone forever" is all it said.

Davis, who borrowed his name-reversing trick from Dracula, Bram Stoker's blood-sucking fiend who introduced himself as Count Alucard, died of cancer in March 2005. He was 92 years old.

Posted By Chris Davis on Wed, Oct 31, 2018 at 12:02 PM

* A version of this article appeared in the Memphis Flyer in 2010 —- but without all the nifty links and embeds.