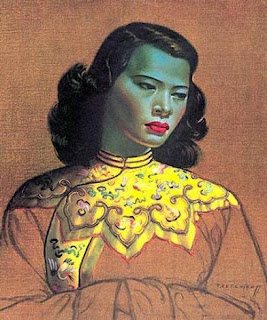

Tretchikoff and the Real Blue Lady

Cabaret singer Tricity Vogue finds the artist who inspired her hit Edinburgh show, and the woman who was his muse

This article was first published in the Erotic Review: The Art Issue in February 2011 http://www.eroticreviewmagazine.com/On my bedroom wall is a 1960s framed print of a woman with a blue-green face, a golden Chinese gown, jet-black hair and startling red lips. I bought it on the Essex Road in North London from a shop called Past Caring. It cost me £70. My mum remembers when the same print sold in Boots the Chemist in Derby for 11 shillings and sixpence. She also remembers that it was the picture everyone wanted on their walls. The Chinese Girl was once better-selling than the Mona Lisa. Vladimir Tretchikoff, the painter, was compared to Picasso and Van Gogh: primarily by himself. The ubiquity of the image for over two decades was also primarily down to the artist himself, thanks to a combination of tireless self-promotion and bullet-proof self-belief. But then, when you’ve survived a revolution, a shipwreck and a Japanese prison-of-war camp, artistic world domination wouldn’t seem beyond you either.

I’ve spent two years painting my face blue in homage to Tretchikoff’s iconic image for my cabaret show The Blue Lady Sings. I had a sneaking suspicion that the man behind this stylised, high-impact portrait might be larger-than-life too, and I was right. Tretchi, as he was affectionately known, has all the ingredients for a quintessential artist profile. Deprivation and adversity: check. Volatile, quixotic temperament: check. Exotic muse and mistress: check. Plus vivid extras, including some uncannily accurate predictions at a séance, and a couple of brushes with death in a pink Cadillac. Tretchi lived his life in brighter colours than everyone else.

It was a long journey to the self-designed mansion in Cape Town where Tretchikoff died in 2006, and one that took in all five continents. It started in Kazakhstan, where he was born in 1913 to landed gentry, before the Russian revolution drove the family to China. There the now-penniless boy earned his keep as apprentice scene painter at the Harbon Opera House until he was sixteen, when the Chinese Eastern Railway commissioned him to paint portraits of Lenin and Sun Yat San for their headquarters, for the princely sum of 500 Roubles. Tretchi used the money to move to Shanghai. In the “Paris of the East” (as near to studying art in Paris as he ever got) young Vladimir bagged both a plum job, as cartoonist for the Shanghai Times, and a wife – fellow Russian émigré Natalie Telpregoff. The couple moved to Singapore in 1936, where Tretchi drew cartoons for the British Ministry of Information’s anti-Japanese propaganda. In 1938 he represented Malaya in the New York World’s Fair, and his daughter Mimi was born. Then the Japanese invaded Singapore and things took on a darker hue.

Natalie and Mimi made it out of Singapore, but Tretchikoff’s later boat was torpedoed while he was stoking the furnace. As the ship sank, he bagged the last place in the lifeboat when a woman thrust her baby into his arms. The forty two refugees rowed for their lives for Sumatra, only to discover the Japanese had beaten them to it. So Tretchi and a bunch of other survivors turned the boat around and rowed another nineteen days to Java, risking drowning, scurvy and starvation en route. Legend has it that Tretchi used drawings to barter with island tribesmen for the coconuts that kept them alive. Their safe arrival in Java palled somewhat when the terrified locals handed them straight over to the Japanese invaders, who’d got there first, again.

The Japanese hauled the whole boatload off to prisoner-of-war camp, but the five-foot-three artist was, like many small men throughout history, pugnacious by nature. Tretchi protested that he was a Russian citizen and the invaders had no right to hold him. They promptly threw him in solitary confinement, where he was stuck for three months. Then the prison camp general offered him conditional freedom – if he turned set-painter for a Japanese gala show. Tretchi basically painted his way out of jail.

Tretchi was living as a free man in Jakarta, and not only free, but also footloose, since his wife and child were somewhere on the other side of the world, if they were alive at all. Enter the beautiful Leonora Moltema, AKA Lenka, half Dutch, half Malaysian, and all woman. The Tretchikoff website describes Lenka as “a woman of culture and intelligence… an artist herself, and mistress of five languages”. The choice of word is apt, since Lenka was indeed Tretchi’s mistress as well as his muse and model. An elderly Tretchikoff told documentary filmmaker Yvonne du Toit in the 1990s that she was the love of his life.

Lenka told her own story to Uri Geller, a firm friend in later years, thanks to their shared interest in the supernatural. Her husband, a Dutch pilot, was, like Tretchi’s wife, somewhere overseas in limbo, and, on the night she first met Tretchikoff, he looked at her across the dinner table in an uncomfortable way, then asked her to pose for him naked. When she bridled at the suggestion, he laughed at her prudishness, telling her that only if every part of her figure was perfect would he consider painting her, and if he did, she would be a lucky woman. Lenka knew “the Mad Russian” already by reputation: by night he painted portraits for 40 guineas a canvas, but refused to sell the canvasses he painted for himself by day. She posed for him every Sunday in his tiny lodgings. It took longer to finish the picture than it did for Tretchi to get Lenka into his narrow bed.

The artist moved in with Lenka, but would only make love at weekends, because he claimed he was unable to paint for twenty four hours after sex. Even less congenially, their love-nest was continually raided by Japanese soldiers, convinced that Tretchi was a spy. One night he was arrested on suspicion of blowing up an oil tanker, and slashed with a ceremonial sword during the interrogation. The superstitious Lenka visited a wise-woman and promised to give up what was most precious to her in exchange for Tretchi’s freedom. When he was released without charge two days later, she gave the old woman her most valuable batik.

But was the batik Lenka’s most precious treasure, or Tretchi himself? It wasn’t long before she had to give him up too. It began when she took him to a séance, at which the previously sceptical painter asked the spirit guide where his wife and child were. The answer came back: S.O.U.T.H. Tretchi subsequently put the Red Cross on the trail of the supernatural tip-off and tracked down his family in South Africa. But before leaving the séance, the artist had a few more questions for the spirits. “Will I become a famous painter, and how far will my fame spread?” W.O.R.L.D. “What will be my most famous painting?” O.R.I.E.N.T.A.L. L.A.D.Y.

Lenka disappears from the official biography of Vladimir Tretchikoff as soon as he set off for Cape Town to be reunited with his wife and daughter. But that is no way to write out a muse from any artist’s story. Luckily she herself has shared a little more with her friend Uri Geller. Tretchikoff went to South Africa with her blessing because, she said, she could compete with any woman but not with his child. She even helped him pack his canvasses, which he’d been hoarding for years ready for the one-man exhibition that he was certain would make his fortune. Lenka extracted one promise from him: to give a canvas to his wife Natalie. He did, and the canvas she chose was the portrait of Lenka wearing a red jacket. “Wearing”, that is, in the loosest sense, since all it covers are her shoulders. Did Natalie know that Lenka had been Tretchi’s de facto wife throughout the war years? Why did she choose to have her love rival’s triumphant breasts pertly waving at her from the wall every day?

Tretchi’s portrait of his mistress is in stark contrast to the portrait of his wife. Like so much of the artist’s work, subtlety doesn’t come into it. Whereas Lenka is a feast of warm naked flesh set off by a “scarlet woman’s” jacket, Natalie The Artists Wife is clad in brown, with skin of a blueish tinge, in arguably Tretchikoff’s drabbest colour scheme ever. Vladimir boasted that living with him was sometimes heaven, sometimes hell, but usually purgatory. “Longsuffering” is the word that springs to mind looking at the portrait of his wife. Who knows? Perhaps his muse Lenka had other reasons for “giving him up”. Maybe two years of keeping house for a fastidious and demanding artist were enough for her.

What’s more, when Tretchikoff took off with his hoarded canvasses on his phenomenally successful world tour (as predicted by the spirit guides, and funded by the spiritualist Rosecrucian Order, in a self-fulfilling prophecy), he was not constrained by the need to paint during the day, and was therefore able to cast off sexual abstention. So Tretchi hooked up with his old flame again in London in 1958. While over 200, 000 people flocked to his one-man exhibition in Harrods, Tretchi took Lenka to bed for what she described as a four-day lovemaking marathon. That’s when Tretchi confessed to his mistress that he had sold the Red Jacket painting, even though theoretically it belonged to his wife so wasn’t his to sell. Lenka was appalled and warned him he would have bad luck without her portrait.

Tretchi took no notice of his mistress’s warning, but not long after his return to South Africa, his pink Cadillac overturned in a road accident. It took a transfusion of 20 pints of blood to bring him back from death’s door. Still Tretchi didn’t buy back the portrait of Lenka until he was nearly killed a second time in another car crash. Then finally he conceded his muse might have a point, reacquired Red Jacket for his wife, and lived to be 92.

As for the Chinese Girl - the painting I bring to life in my cabaret show, and the one looking down at me mysteriously from my bedroom wall – it isn’t Lenka. At least, not officially. The first model for the painting was said to be a member of South Africa’s Chinese community. But according to other accounts, the painting, completed in 1950, was begun in Java in 1946, before Tretchikoff got to South Africa. To complicate matters further, the portrait we know is not of the first sitter anyway. The original canvas of the Chinese Girl was slashed, along with 14 others, when intruders broke into Tretchi’s Cape Town home, enraged by the artist’s controversial drawing Black and White, which caused outrage throughout Apartheid South Africa.

The second model for the Chinese Girl was reputedly the daughter of a restaurant owner in San Francisco. Yet there is something Eurasian about the features of the woman with the blue-green face in the painting. By 1950 when he finished the picture, Tretchikoff had been apart from his half-Dutch, half-Malaysian muse for four years. And South Africa was a long way from the oriental lands where he had first found the inspiration to paint. Tretchikoff himself said his paintings were not real women’s portraits, but a fantasy of womanhood from his own imagination. Whoever sat for him in a golden Chinese brocade gown, whether in South Africa or in San Francisco, the real “blue” woman who epitomised longing and absence in the artist’s imagination wasn’t either of them. It was Lenka, the woman who wasn’t there.

Tricity Vogue’s debut album, The Blue Lady Sings is available from her website: tricityvogue.com

Her one-woman show will appear at the Brighton Fringe Festival in May 2011, and the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in August 2011.Photograph of Tretchikoff and Lenka by kind permission of Yvonne du Toit

All other pictures by kind permission of the Tretchikoff Foundation